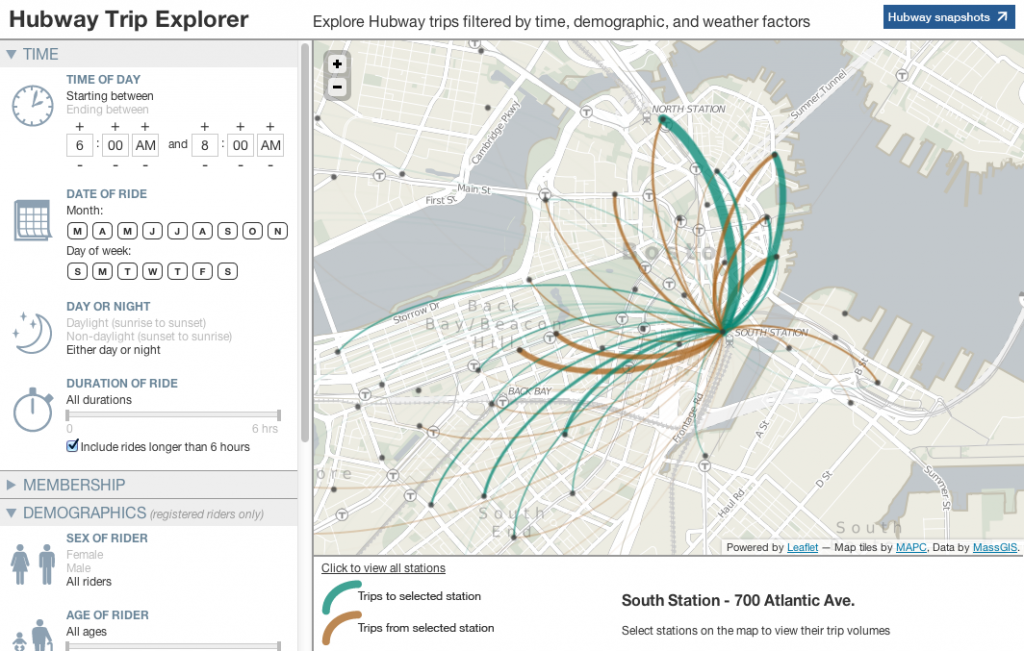

As an occasional Hubway user, I sometimes feel like some kind of transportation gambler. There’s a risk with each trip. Will docks be available where I’m going? Will bikes be available when I want to return, and docks available back home? A losing bet can pretty easily turn a 10 minute bike ride into a 30 minute walk, or some kind of multiple-transfer MBTA nightmare. This is especially true if the trip is going to or from an area without redundant coverage, where there is no second station within convenient distance of the origin or destination.

My potential Hubway trips are frequently to the same place (Inman Square, specifically Parlor Sports of course) and at similar times, so I wondered if the station I want is always freakin’ full, or only often full at the time of day I want it. Or, more generally: when and where is Hubway generally available or unavailable?

By hitting the station data feed regularly, it’s possible to keep track of the availability of bikes and docks over time. This is done masterfully over here, where you can see charts showing when during the current day each station was totally full or totally empty. (Or see the summary of the previous day, and the links at the bottom to the same for many other cities.) Notice the green slivers showing times when every station in the system has both bikes and docks available—it turns out that 100% Hubway availability usually only occurs for a few minutes each day.

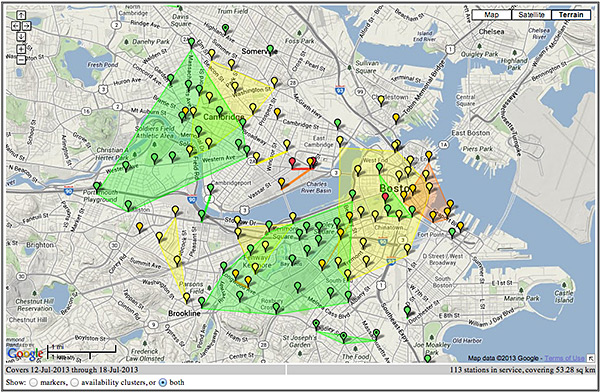

Of interest to a cartographer, too, is the basic map of overall Hubway availability (above) that colors each station according to how often it has both bikes and docks available and furthermore calculates some clusters of similar availability. I was motivated to expand on this idea to longer patterns by collecting more data and breaking it into a couple of different measures and multiple time slices.

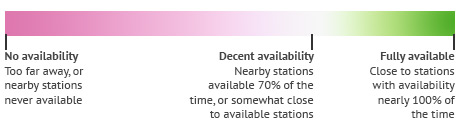

So using approximately the past month of data, below is a series of maps of access to the Hubway system. A few observations follow at the end, but first a bit about the maps. They mostly represent the percent of time during which Hubway stations are available for use. They show a calculation of accessibility based on the following:

- Distance: Hubway bikes are not available to you if you are too far from stations, obviously. For this part, 100% accessibility is assumed within 1000 feet of a station, and then it drops off farther away until somewhere around 1 km, at which point one is assumed to be beyond Hubway access. A simple distance map is overlaid on the interpolated availability maps described below.

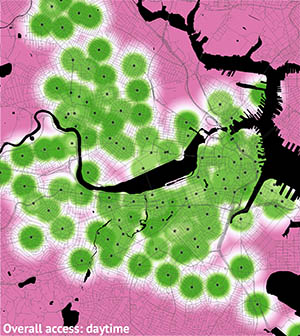

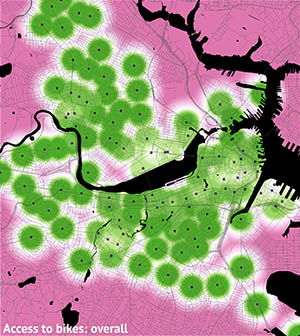

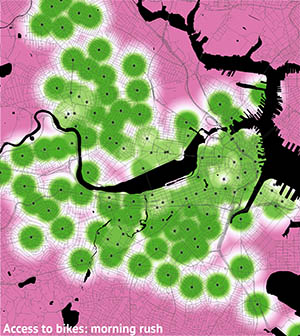

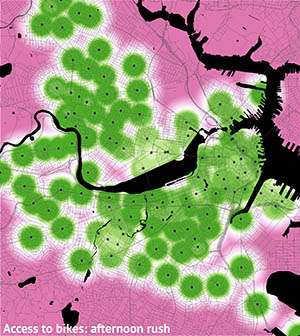

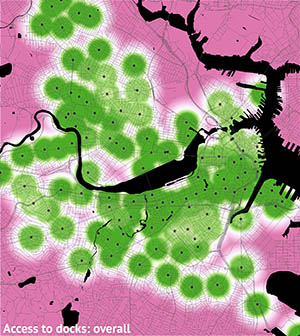

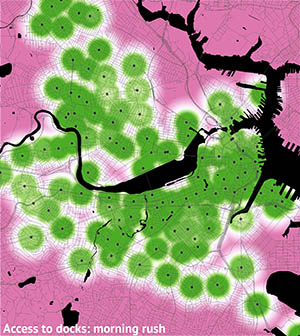

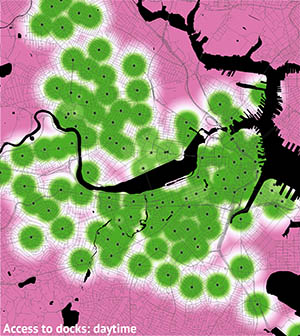

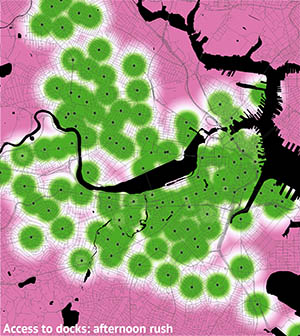

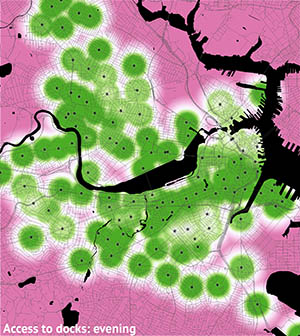

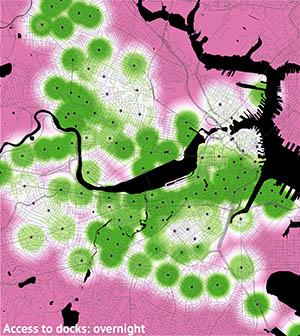

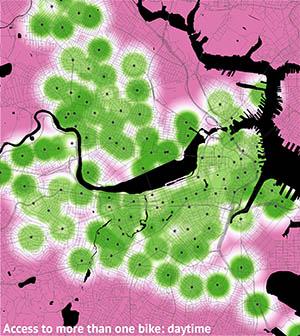

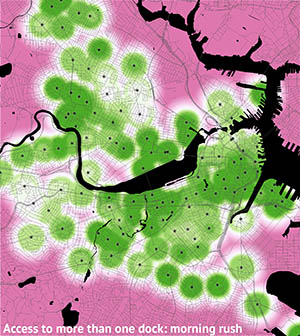

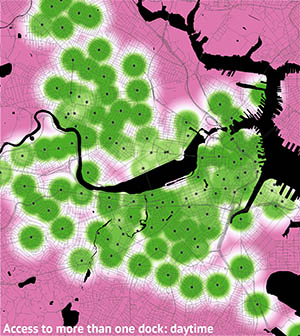

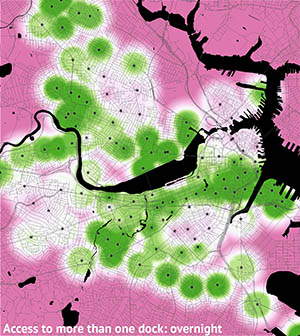

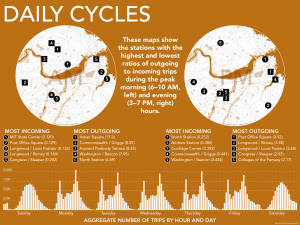

- Time: Like any transportation system, Hubway sees different usage patterns during different times of day. The small multiples show how availability changes throughout an average day. The time slices are the morning rush (6–9 AM), daytime (9 AM–4 PM), afternoon rush (4–7 PM), evening (7–11 PM), and overnight (11 PM–6 AM).

- Station availability: This is the percent of time when stations were available. Availability is defined in three ways, each with its own set of maps.

- Number of bikes available: If there are no bikes at your departure station, you can’t go anywhere, or at best you have to walk to the next closest station.

- Number of docks available: If there are no empty docks at your destination, you’re in trouble, i.e., you can’t get there from here.

- Number of docks and bikes available: The “overall” maps count a station as unavailable if it is either full or empty.

Overall access

Access to bikes

Access to docks

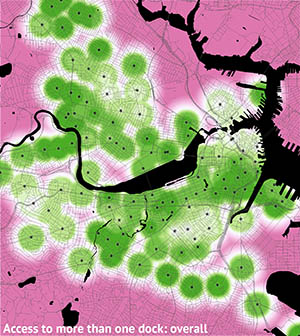

The maps above are all based on times when the number of bikes and/or docks was greater than zero. But if you’re like me, nonzero isn’t an assurance of availability. If I’m headed out and see that only one dock is free at my destination, it feels like a big risk. With that in mind, below is a series of maps based on a more comfortable margin: if a station has only one bike or one dock, it’s treated as unavailable.

Overall assured access

Access to more than one bike

Access to more than one dock

Having looked through all of that, a few observations:

- There are gaps in Hubway coverage. Not that we needed these maps to know that, but besides the fringe areas, some of the interior is not well served, such as Cambridgeport and some of Brookline.

- Daytime accessibility is good. In most scenarios, station availability is high and the maps are not easily distinguishable from a simple distance map.

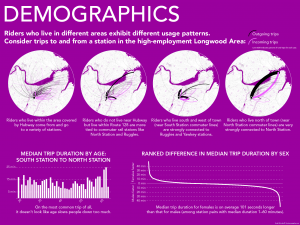

- Availability isn’t great in some high-employment areas. Probably the most dramatic thing in these maps is the emptying of Kendall Square in the afternoon. It makes sense that people would leave such a high-employment area in droves at the end of the day, but the Kendall area has also recently become a restaurant and bar hot spot, and Hubway bikes are not so reliably available during their busy evening hours. Similar patterns can be seen in the Financial District, the South Boston waterfront, and the Longwood area. Perhaps these places could use larger stations or more concerted rebalancing efforts.

- Overnight: good luck! Access to docks during overnight hours—and bear in mind that much of this time is when the T doesn’t operate—is often limited in residential areas. If you’re out late and need to get home to Somerville, Cambridge, Brookline, Allston, Charlestown, the North End, or the South End, you may be in trouble. Usage overnight is low, granted, so it’s unlikely for someone to swoop into the last available dock before you do, but the stakes are high.

Overall the system is usable; there are few if any cases where stations aren’t available at least a majority of the time. And it’s a fantastic addition to the city’s transportation modes. But in a lot of situations it can’t be relied upon as the only transportation option. Never mind that it doesn’t even exist for a quarter of the year—you just never know when someone’s going to beat you to that last bike!