The other day a colleague asked me, “Hey Tim, how do you make one of those Google Maps with a pin in it so I can show my friends how to get to my birthday party?” I knew he was joking for two reasons: 1. His birthday was months ago, and 2. He is well aware of my fascination with digital pushpins. Nevertheless, this mock question resulted in an interesting realization (take that, Ricky!).

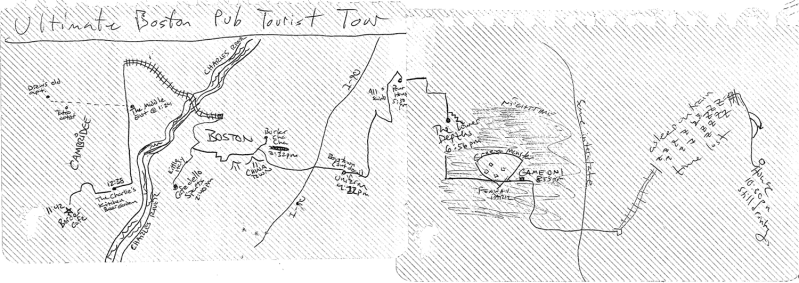

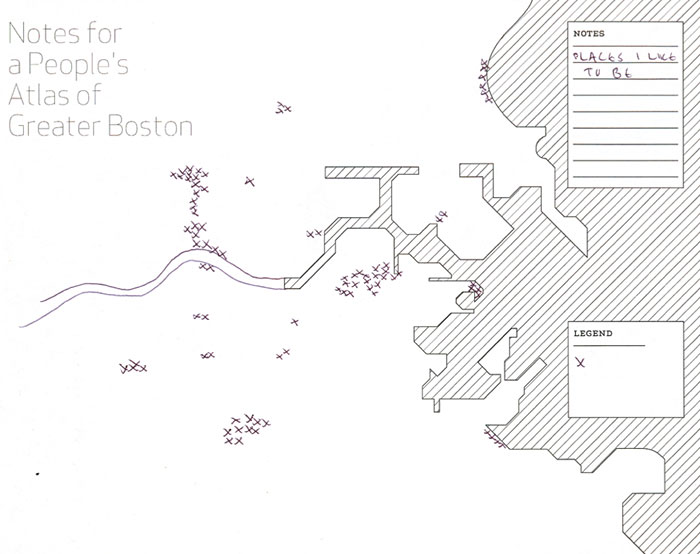

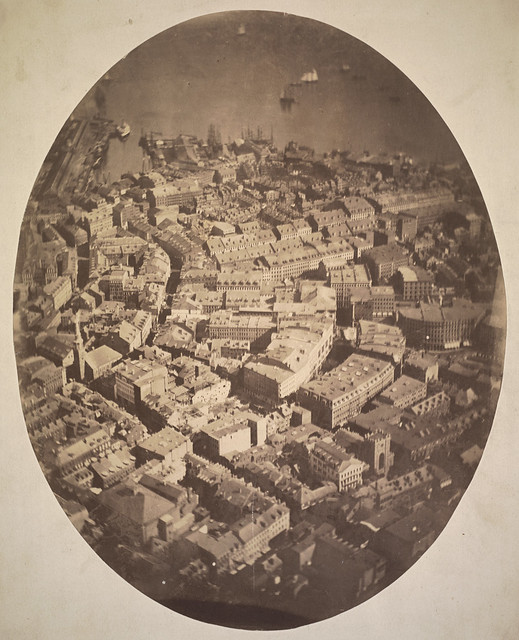

Digital maps have done all kinds of wacky things to the way we interact with spatial representations and how we imagine our surroundings. But one thing that hadn’t dawned on me until this conversation was that the sketch map may well be an endangered species of cartographic representation. I found the map below on Flickr with the caption, “Map I drew for my dad while we were having a beverage at Quincy market showing where things were in Boston.” This is great, right? A casual conversation required some visual aid, and a sketch map was employed. But would all fathers and sons nowadays have done this?

The need to sketch a map on a napkin or the back of a receipt to show a friend how to get to your favorite coffee shop is slowly disappearing like Marty McFly’s fingers in Back to the Future. Increasingly, we share locations through some mobile application, or we send a link to a digital map where the location is highlighted, or, if we have any faith in our friend’s ability to use technology, we simply… tell her the name of the location. After all, she can look it up just as quickly as we can, right?

Finding things—coffee shops, candy stores, ball parks, bowling alleys, Grandma’s house, &c.— has become so easy that the sketch map (made for directing or orienting someone to a place) may no longer be necessary. I know, I know—this is not news. Digital maps, GPS and (even if more recently) place-based mobile applications have been around for a good long while. But while everyone is jumping on the bandwagon of new spatial technology and communication, it seems no one is stopping to ask: what are we losing when we click on a Google Maps link instead of poring over a friend’s sketch map?

I bring this up because I think we are losing quite a bit. Why does our friend like this place? How does he imagine the neighborhood? What is most important to him in that neighborhood? What does he exaggerate? What does he forget? All of these are questions that cannot be addressed the same way through a weblink (these unanswered questions are the notes Marty McFly misses on his guitar as his fingers disappear).

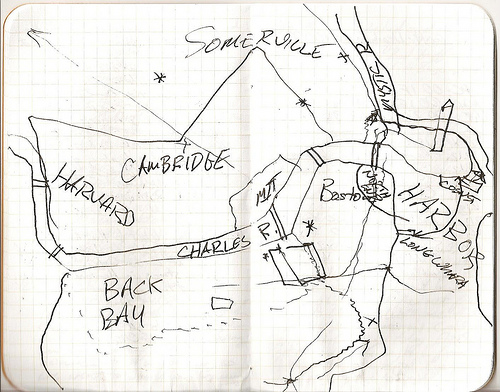

Perhaps some people do not care about these questions—or at least don’t care enough to specifically want to explore them through sketch map-based communication. But I do. And it turns out I’m not alone. Check out the Hand Drawn Map Association (HDMA), an “ongoing archive of user-submitted maps and other interesting diagrams.” These folks are collecting sketch maps of places all around the world, and helping to keep maps like these from going completely extinct. Once you’ve visited awhile, why not draw a map and submit it? You might learn something about the way you view your world.

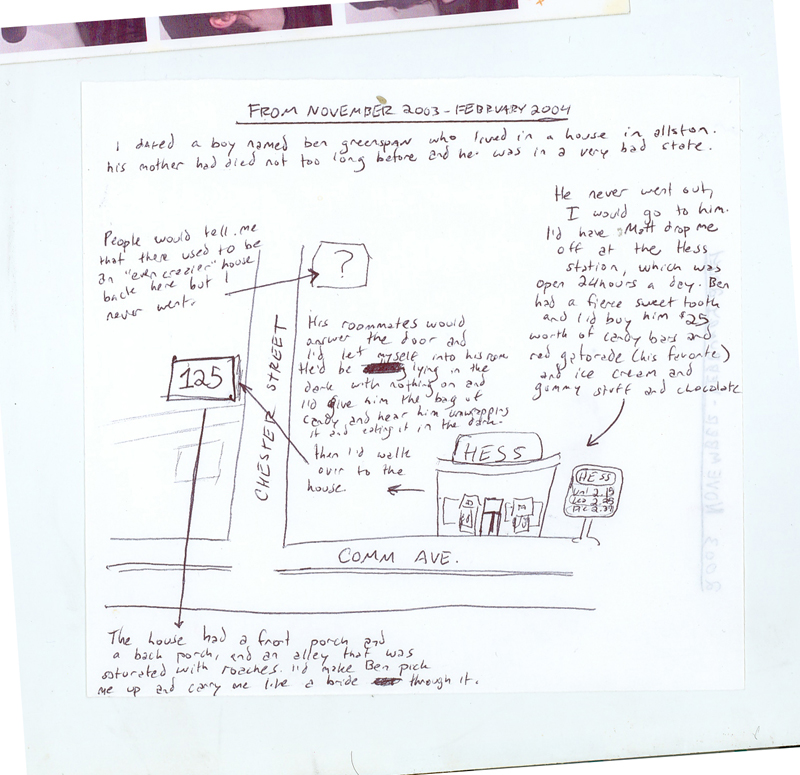

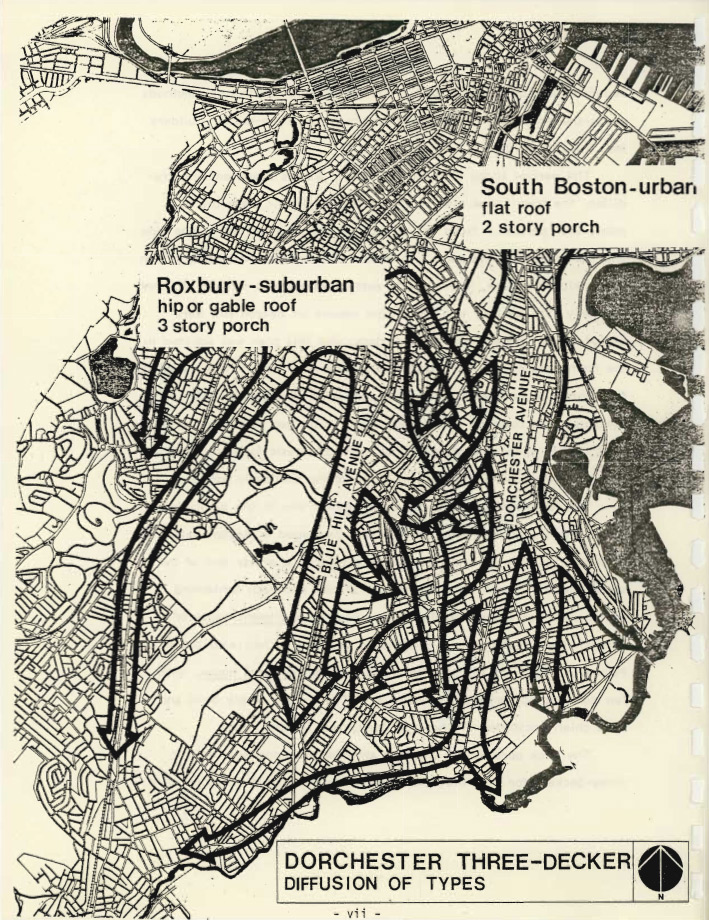

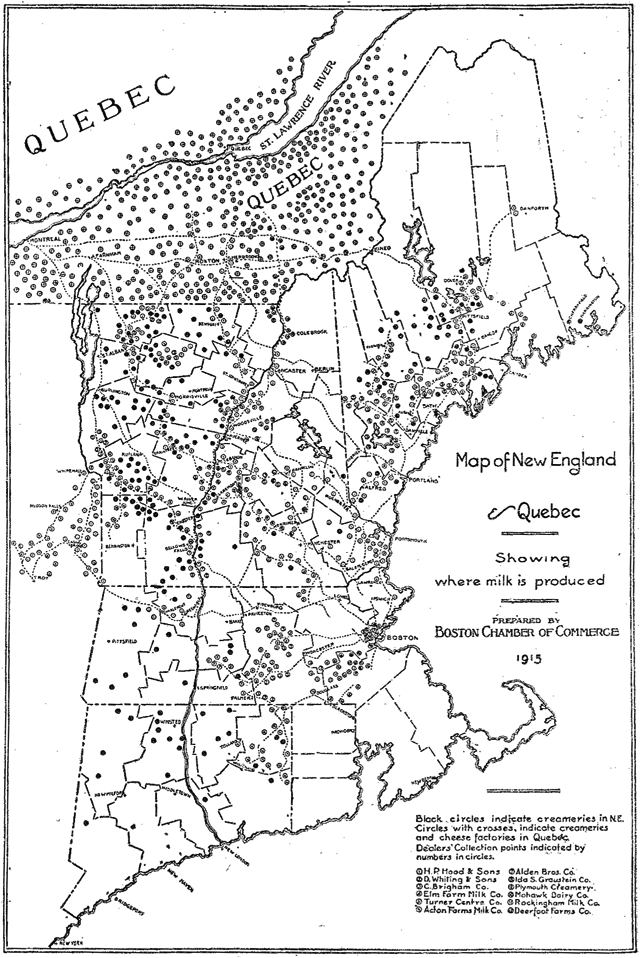

Here is a typical map found on HDMA. Based on the roads in this map, I think I know this place (and I’m resisting the temptation to include a link to a Google Map that locates it for my readers). But I definitely don’t know it the way that it is portrayed here. I bought my first car across the street from this intersection, but I remember no Hess station. So who’s wrong? Me? The guy who drew this? No—neither of us are wrong. This is a sketch map; the author’s representation of that space as he remembers it. Unless spatial accuracy is the main goal of the sketch (which it rarely is), it is no more or less valid than the way anyone else imagines that space (but, still, I swear there wasn’t a Hess station there the last time I checked!).

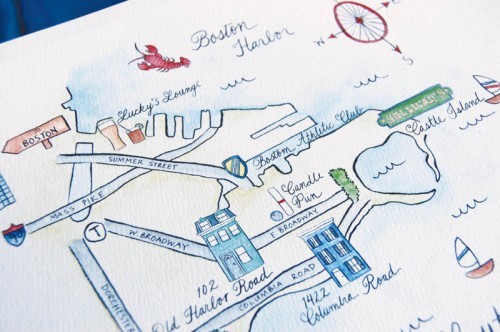

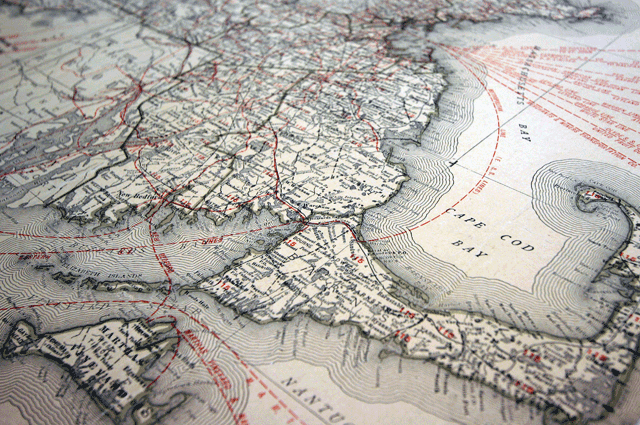

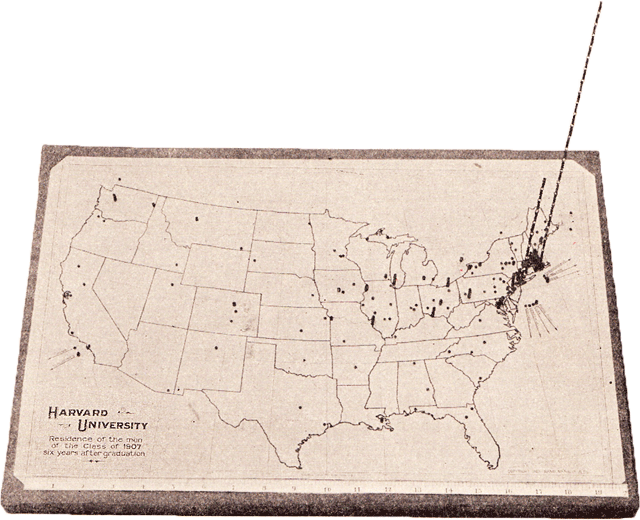

Another force keeping the sketch map from going the way of the dinosaur is the “art map,” a vague genre of map that includes everything from Nantucket-shaped coffee spills to wood–carved block diagrams. (In other words, anything that is artistic—as if that were something that could be determined objectively.) While people do seem to have developed a dependence on digital maps because they are convenient (to say nothing of hip and “futuristic”), they have not given up their fascination (or even obsession) with “artistic–looking” maps. These often come in various forms of would–be wall hangings: painted pin maps, watercolor maps or stained glass maps. Thankfully, many of these maps are created by hand, and just maybe serve as a reminder to those who did not create them that perhaps they could try.

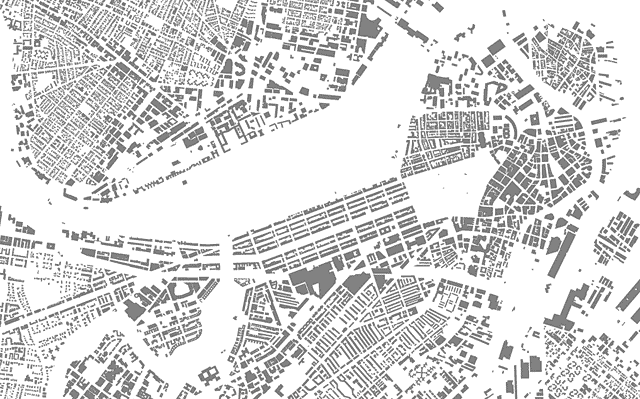

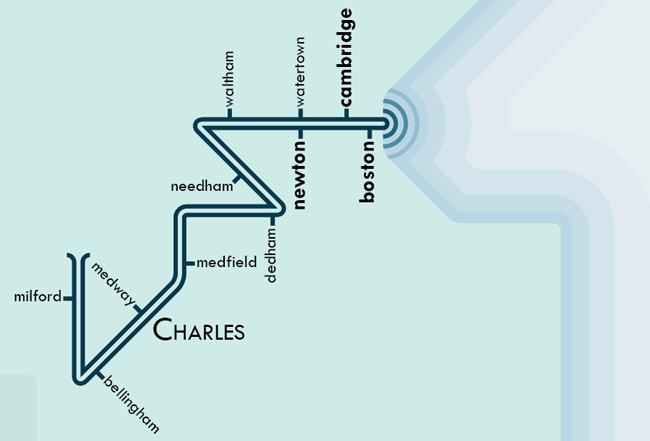

One place we find plenty of art maps these days is in that calligraphy-emblazoned triple-thick envelope dropped in our mailboxes two or three months in advance of a loved one’s wedding. Above is a watercolor map made for a wedding in Boston. Nice map, right? Is it spatially accurate? Meh… who cares?! It’s beautiful and it’s personal.

It’s my hope is that these sorts of works inspire more people to make maps by hand. So the next time you’re sitting in the South Street Diner and plotting your day with some buddies, think twice before whipping out your smart phone. Map it out on napkin and send it to us. We love this stuff.