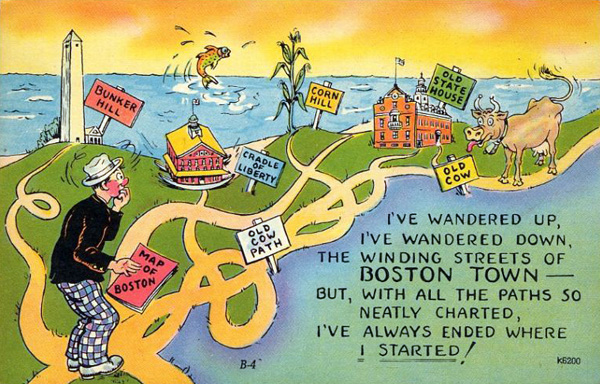

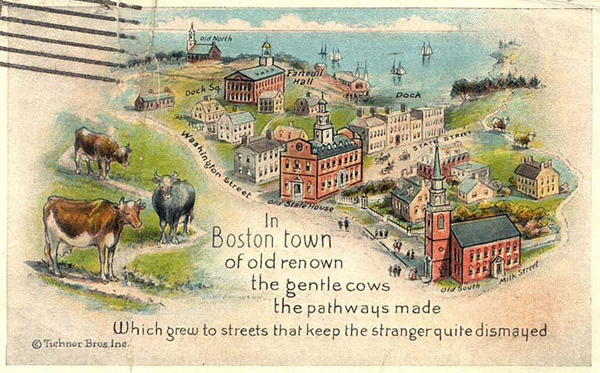

You’re walking around Boston and a friendly stranger approaches you. “Say, I’m new in town. What neighborhood is this?” she asks. You furrow your brow, laugh nervously and say, “Back Bay? South End? Possibly both… or neither.” Then, for fear of coming off like a grade-a jerk, you apologize and explain that Boston is notorious for being a geographically confusing place to newcomers. You go off on a tangent about how you blame colonial cart paths and Frederick Law Olmsted’s string of Emerald Necklace parks for the wonky non-grid that makes up much of Boston’s city streets. By the time you finish your tirade, your new friend is gone.

You are a little disappointed that you couldn’t share more, but you understand. Boston is a city that evokes all kinds of emotions in its inhabitants and visitors. You are no exception. You have a real sense of Boston. You live there. You navigate its paths on a regular basis, visiting landmarks and nodes of activity within city districts. You even cross over intangible edges between neighborhoods and along the outskirts of town. And all of this adds up to your mental image of the city. How you live in your city, how you experience and cognize its time and space, and how it is imagined by you and your fellow inhabitants is the heart of the research of the proto-Bostonographer, Kevin Lynch.

Kevin Lynch was born in Chicago in 1918. This might seem like an unnecessary detail, but I believe it had some bearing on his professional career. During Lynch’s adolescent years, Chicago was a hotbed of cutting-edge (landscape) architecture and design. Art Deco was in full swing, with the Tribune Tower being declared “the most beautiful and distinctive office building in the world” in the 1920s. Beaux-Arts style buildings were also making an impact on the Chicago landscape. The London Guarantee Building and 35 East Wacker Drive (“The Jeweler’s Building”) are two examples of this style that continue to influence the way natives imagine their city.

To grow up witnessing the Chicago landscape reinventing itself year after year must have had some influence on Lynch and how he imagined the urban environment. But the path Lynch took from high schooler to urban planning visionary was less than direct. Between 1935 and 1948, lynch spent time at Yale (studying architecture), in Wisconsin (studying more architecture under Frank Lloyd Wright), at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (studying engineering and biology), in the South Pacific (as a member of the US Army), in The Philippines and Japan (as a member of the Army Corps of Engineers), at MIT (getting a BA in urban planning) and in North Carolina (as a practicing urban planner). Oh, and he spent some time in Florence for good measure.

You can see the pit stops in Lynch’s life brought out in his works. But the stop (or, really, terminus) in which we are most interested is that of Boston. In 1948, at the behest of his wife (who was vocal about preferring Boston over Greensboro, North Carolina), Lynch took a faculty position at MIT. And it’s lucky for Boston that he did, because he used his new hometown as a case study in much of the research he did from that point forward.

Lynch’s most famous work, The Image of the City, was published in 1960. It proved to be an approachable little book that – through its quirky illustrations and clear and concise explanation of the process of perceiving one’s landscape – has inspired geographers, architects and planners for decades. The Image of the City was the product of field work that he performed in Boston (as well as Jersey City and Los Angeles) from 1954 to 1959 on the project The Perceptual Form of The City. Lynch and Professor Gyorgy Kepes (also of MIT) conducted interviews, made field sketches and took photographs all in an attempt to get at how city-dwellers perceived their landscape.

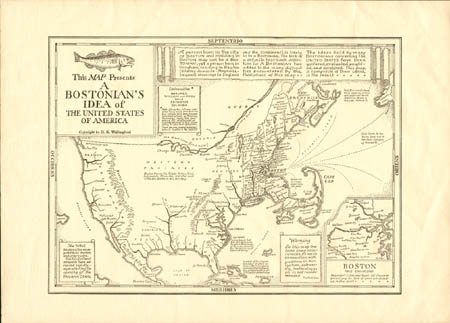

Scholars generally refer to The Perceptual Form of The City as a seminal “mental mapping” project. But it was much more. Mental maps are great (goodness knows, I’m a huge fan) and getting a glimpse of how minds store space is fascinating. And in that vein, sure, Lynch was interested in putting the maps from Bostonian minds on paper (as he did in numerous and compelling ways), but he was also interested in the way people experienced their landscape and soaked up their city. Lynch wanted to know how people sense their city and how they use that sense to go about their lives within it. If such a thing was knowable, Lynch believed it could be leveraged in future planning efforts.

For Lynch, key to the process of teasing out the individual and collective perceptions of a city was the concept of imageability. You may have noticed by now that many of these concepts are fairly fluffy, based on feelings or impressions rather than – well, science. But that’s the whole point. Lynch and planners of the Lynchian School (if one exists) are more interested in the sense of people who live in the space than the science behind the stuctures within it. That said, “imageable” is a term Lynch invented to indicate how well a place can be taken in, mentally mapped, experienced.

A highly imageable city… would seem well formed, distinct, remarkable, it would invite the eye and the ear to greater attention and participation. The sensuous grasp upon such surroundings would not merely be simplified, but also extended and deepened. Such a city would be one that could be apprehended over time as a pattern of high continuity with many distinctive parts clearly interconnected. The perceptive and familiar observer could absorb new sensuous impacts without disruption of his basic image, and each new impact would touch upon many previous elements. He would be well oriented, and he could move easily. He would be highly aware of his environment. The city of Venice might be an example of such a highly imageable environment. In the United States, one is tempted to cite parts of Manhattan, San Francisco, Boston, or perhaps the lake front of Chicago.

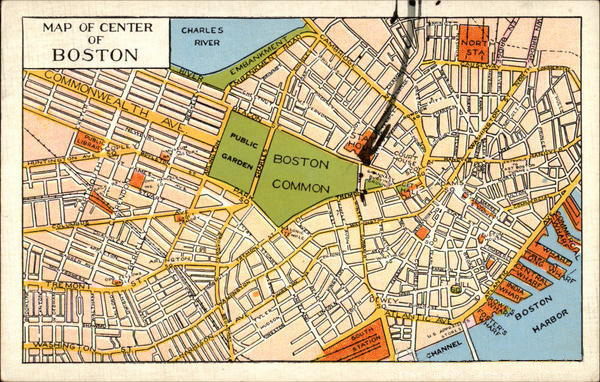

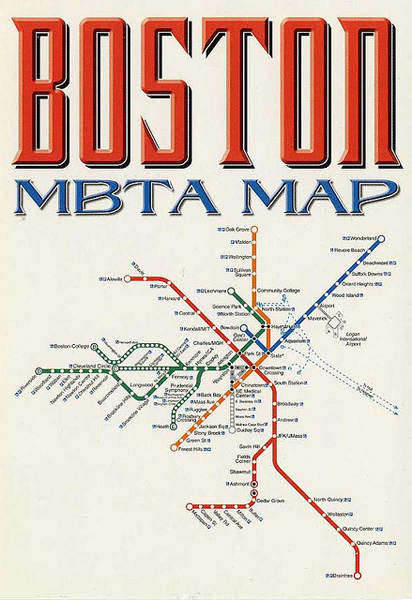

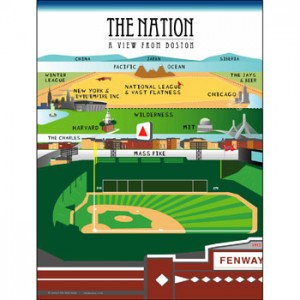

Now, I could see some Bostonians taking exception to the high imageability of their home city. Lynch points out that a person should be well oriented and highly aware of their environment in an imageable city. But it’s no secret that newcomers are often confused and disoriented by the crooked streets of Boston. Newcomers also complain about how misleading transit maps are, when a 20 minute subway ride would have been a 5 minute walk. But does this debunk the high imageability of Boston? No – these things are true of many cities.

What makes Boston so highly imageable isn’t that it is easy to navigate; it’s the prominent and memorable components of the city. One might not know the most direct route from Fenway to The North End, but a mental map of the city may still contain depictions of the Citgo Sign and the entrance to the Callahan Tunnel. Lynch breaks the perceptual city up into handy and easily understood components. He believed that cognitive maps and the mental images that people compile about the space around them are mainly composed of paths, edges, districts, nodes and landmarks (none of which are mutually exclusive).

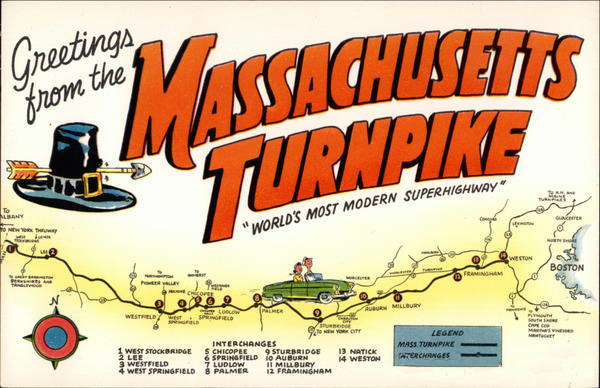

Lynch loosely describes paths as “channels along which the observer customarily, occasionally, or potentially moves. They may be streets, walkways, transit lines, canals or railroads.” This concept should be immediately familiar to anyone who has ever lived… well, anywhere. The route you take to walk your dog, your favorite weekend bike loop, the Silver Line bus route – these are all paths that potentially help shape your perception of space and place.

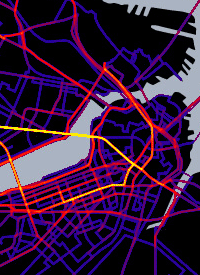

With paths in mind, you can see how Boston would be a highly imageable city. After all, Boston is an incredibly walkable city. Lynch would accept established paths in this framework, like those through the Boston Common and Public Garden, or even the Freedom Trail. But paths can also be personal – paths to grab tea, paths to your buddy’s office, quiet paths, loud paths, fast paths, paths to the T, etc. In Boston, we have these paths. With a large enough number of paths, a greater mental grid is perceived, while the uniqueness of each path is retained.

Lynch describes edges as, “the linear elements not [necessarily] used or considered as paths by the observer. They are the boundaries between two phases, linear breaks in continuity: shores, railroad cuts, edges of development, walls.” He goes on to point out that edges are not always impenetrable and, in fact, are often seams between two districts or areas.

Boston is loaded with edges. Lynch cites the Charles River as the most prominent example. Though the Charles may be considered a path by kayakers and rowing teams, the vast majority of Cambridge and Boston inhabitants are likely to treat it as an edge. It certainly functions as and edge on my cognitive map of Boston. Other edges in Boston might be the historic central artery or The Fens as well as Beacon, Tremont, Boylston and Arlington streets surrounding the Boston Common and Public Garden (or even Charles street, separating the two).

Edges often (but not always) separate what Lynch calls districts or, “medium-to-large sections of the city, conceived of as having two-dimensional extent, which the observer mentally enters ‘inside of,’ and which are recognizable as having some common, identifying character.” Districts, like paths, can be official or political, but I would argue that they could also depend largely on the individual who is perceiving the surroundings. “My neighborhood,” for example, could be considered a district that may or may not overlap with other districts.

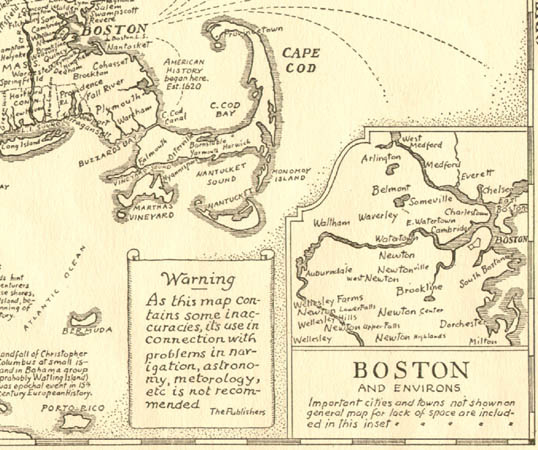

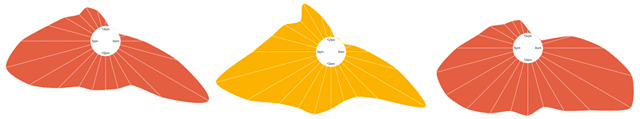

The map above is a rough consensus map of districts that existed in Boston in the 1950s. The hard line represents the minimum agreement area, while the dashed line represents the maximum area. The overlapping areas cause confusing situations like the hypothetical dialogue above. Examples of districts in Boston include Beacon Hill, Back Bay and the South End.

Lynch refers to two distinct types of nodes. Some nodes are junctions of paths and are therefore often transportation-related, while others may simply be a concentration of some type of use or characteristic. Nodes are important to the whole of how a city is perceived because they are related to the concept of path, since they often represent path junctions. They are similarly related to the concept of district since junctions are often prominent features within them. Lynch asserts that nodal points are to be found in almost every mental image of a place, and in some cases they may represent the most dominant feature.

Imageable nodes in Boston abound: South Station, Copley Square, Kenmore Square, Back Bay Station, etc. Lynch also refers to Louisburg Square as a node, though I might argue that nowadays there simply isn’t enough (auto or foot) traffic to constitute this designation (which he bases on the homogeneity and enclosed nature of the square). Nevertheless, it could be argued that Lynch (and this is something I definitely agree with) is remarkably loose with his “definitions”, erring on the side of “no wrong answer” in human perception.

A landmark is an element within the city that – like a node – is a point-reference. But in the case of a landmark, the city-dweller only observes and does not normally pass through. In other words, if Kenmore Square is the node, the Citgo Sign is the landmark. Landmarks can vary in size from a distant hill to your next door neighbor’s doorknob.

The gold dome of the State House, The Custom House tower, The John Hancock and Prudential Towers, and – of course – the Landmark Center in Boston all represent possible landmarks. But these are obvious. Parking meters, grave stones, T entrances, and fence posts can all be landmarks too. I might even argue that a person who you often see in the same place could be a landmark (you know you are getting close to Back Bay Station when you see the “Animal Cruelty” lady, for example).

Past Landmarks have a particularly interesting spot on the collective mental map of Boston. Who, for example, hasn’t gotten directions in Boston based on “where the old Gulf station used to be”? It’s a shame they don’t program GPS devices to give directions based on long-gone landmarks. They would surely be a hit with long-time Boston natives.

So this is how a city is perceived according to Lynch. The inhabitants sense their city, in whole and as a sum of its paths, edges, districts, nodes and landmarks. You might wonder how Lynch managed to unpack such a complex idea into such understandable terms (and in a way that makes us feel like we knew it already). The fieldwork that took place as a part of this study was remarkably exhaustive and holistic. Lynch didn’t just doodle mental maps. He conducted countless interviews on how people experienced their surroundings (what Boston looked like, how it sounded and – yes – smelled to them). One such interview offers a vivid account of the way the light hits the buildings where the pigeons hang out and rambles on to Boston’s “odd skyline”.

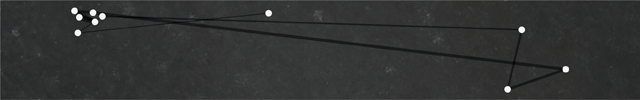

Lynch also collected memory maps, a sort of mental map that is drawn some time after a place is experienced. These were drawn following biking and walking tours. He did this with his students (here is an interesting example that synthesizes many student maps) and research associates (here is an example showing what could be mapped 12 hours after a walking tour).

Another part of The Perceptual Form of the City project was to have Boston extensively photographed. When paired with the interviews, these photographs offer an eerie insight into the mental maps of Boston’s 1950s inhabitants. Some of the photos are taken every few feet along a sidewalk and are careful to include major paths, nodes and landmarks. Watching them in sequence is like mimicking the act of walking and mentally mapping.

In addition to some of the more obvious photographs (like most images in this post), the photographer captured some brilliantly subtle elements to the visual landscape, including several images of visual limits. This set of unassuming landmarks and visual limit images comprised shots of sidewalks, grass, fences, cobbles, walls and advertisements.

Lynch is primarily known for The Image of The City, but he continued to teach at MIT and produce equally fascinating work for decades after it was published. In one such book, What Time is This Place?, Lynch eloquently discussed how time is experienced and absorbed in the urban landscape. Instead of relying too heavily on the historic nature of Boston in this volume, he pointed to more commonplace ways the passage of time was being perceived in the city (footprints in concrete as a snapshot in time, observing what people are carrying as an indication of the time of day, trees as seasonal clocks, &c.).

Less than a decade after Lynch passed away in his summer home on Martha’s Vineyard, a collection of his works was published by The MIT Press. The anthology, City Sense and City Design, is jam-packed with great material, much of which concentrates on Boston and the Boston metro region (including a proposal for new planning practices written with the Boston Redevelopment Authority). One of the more wacky (at least from a post-Cold War perspective) projects Lynch got into later in his career involved mapping what would happen if Boston were hit by a 1-megaton nuclear bomb. For a time, he was also quite interested in humans, waste and space.

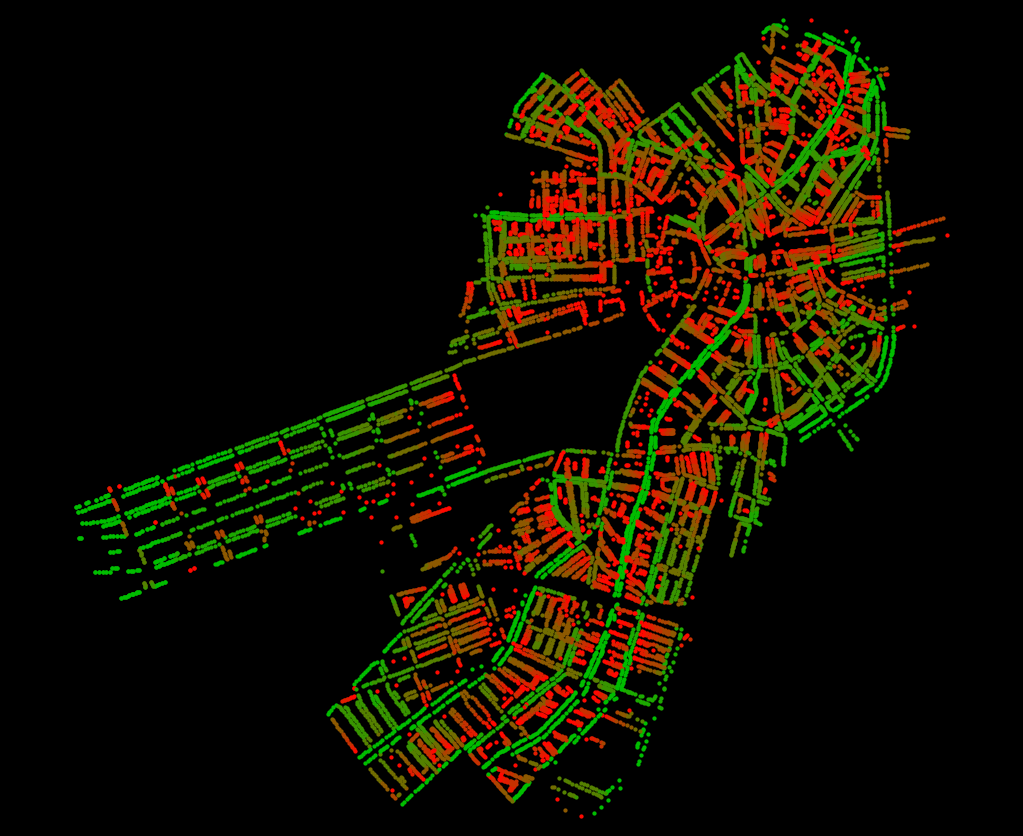

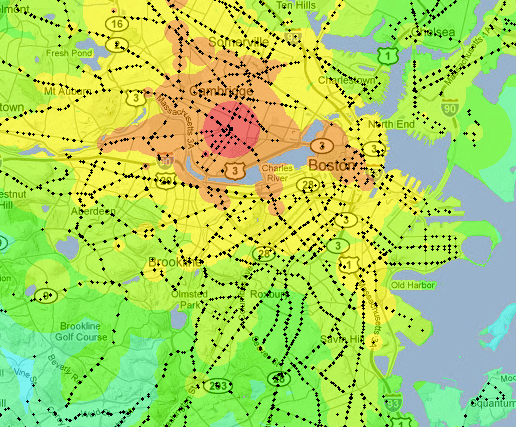

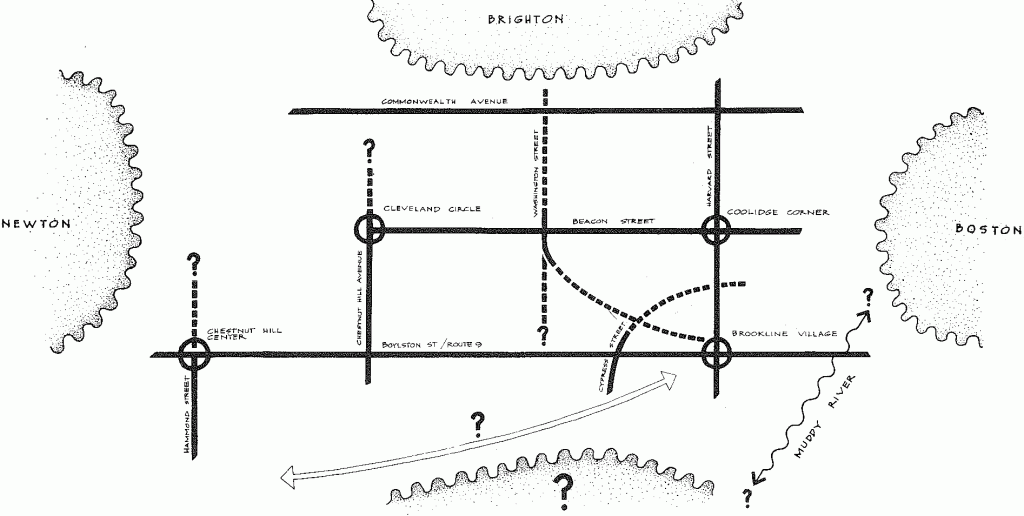

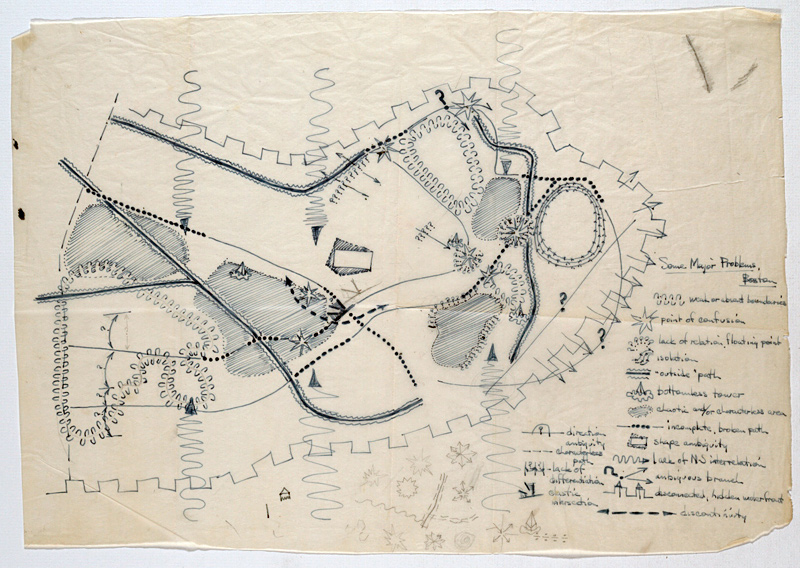

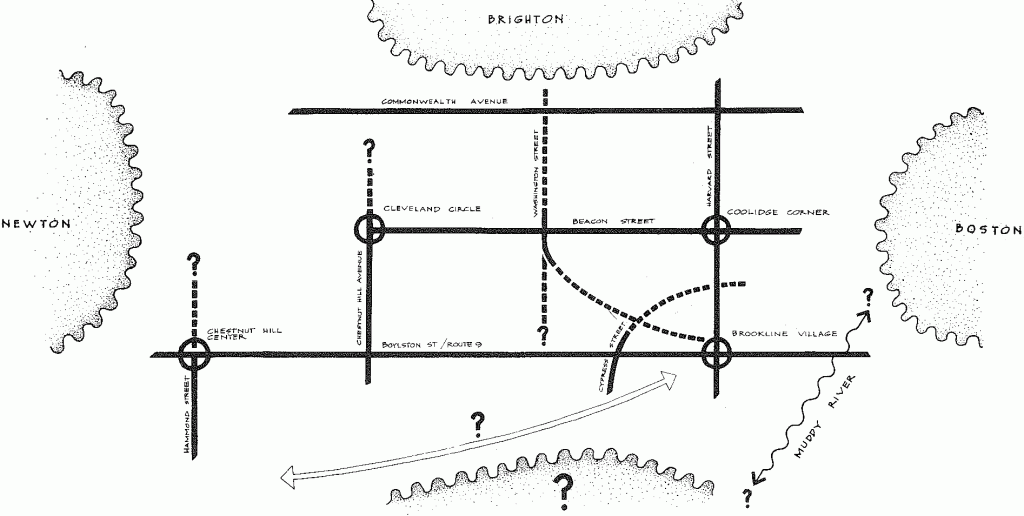

What I will leave you with here, though, is a map of a place just outside of Boston, a place that is in fact often confused with Boston. In the mid-1960s, Lynch performed a project entitled Visual Analysis: Community Renewal Program for the town of Brookline, Massachusetts. The goal of the project was to reveal potential problems in the way inhabitants perceived their town (with the idea that perhaps some of these problems could be remedied). The map below represents the collective public image of Brookline based on interviews performed as a part of the project. What do we think, Bostonographers, has this perception changed much since 1965?

Note: Lynchian paths and nodes that make up the town while fuzzy edges and districts are in the distance (my favorite being the question mark to the south that could still in be Brookline).