The 2023 MLB All-Star Game is tonight and the Red Sox are sending a single representative, closer Kenley Jansen. Since it may not be the most riveting game for Red Sox fans, let’s turn our attention to the place where geography and baseball trivia meet—Red Sox, Massachusetts.

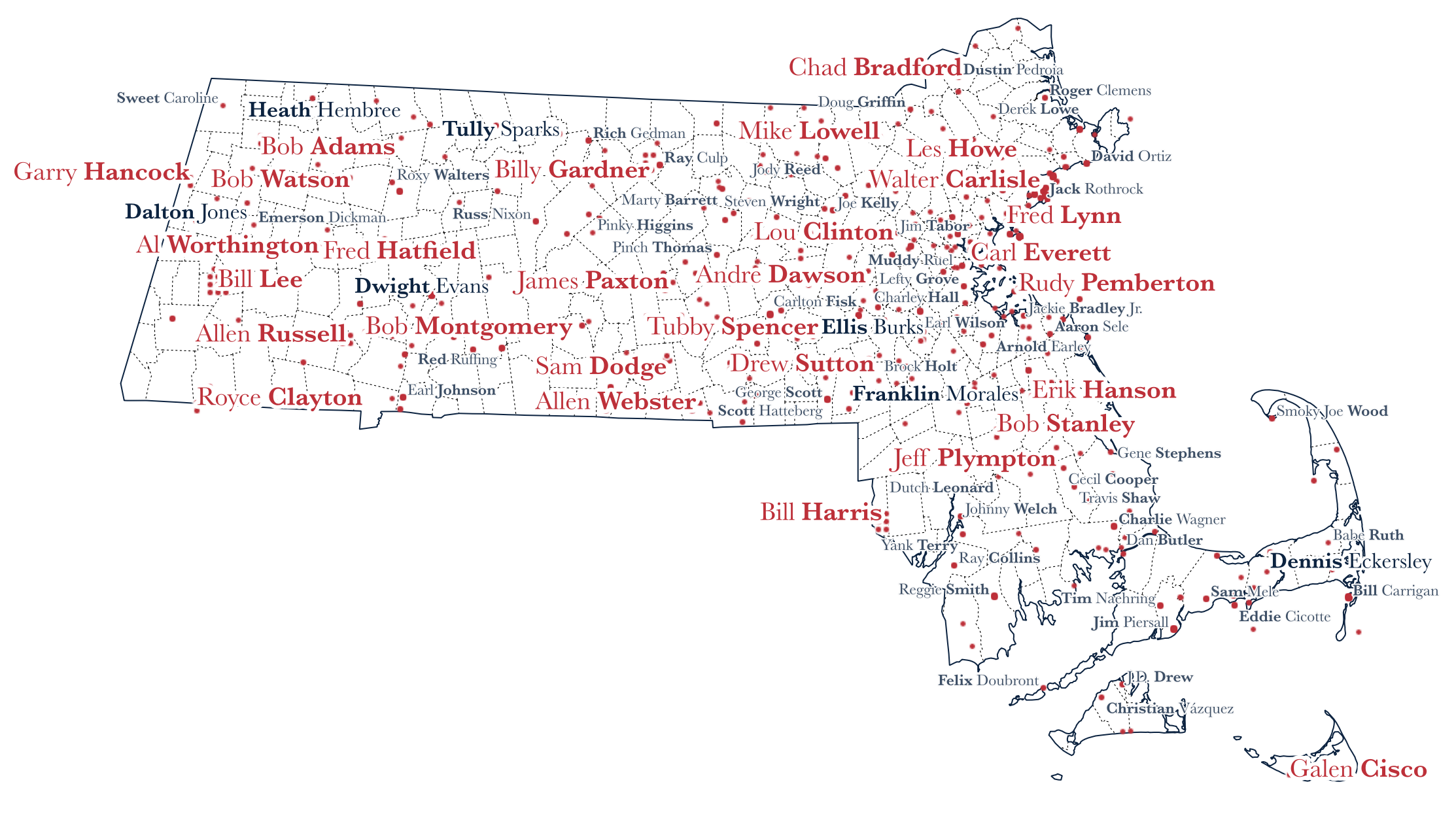

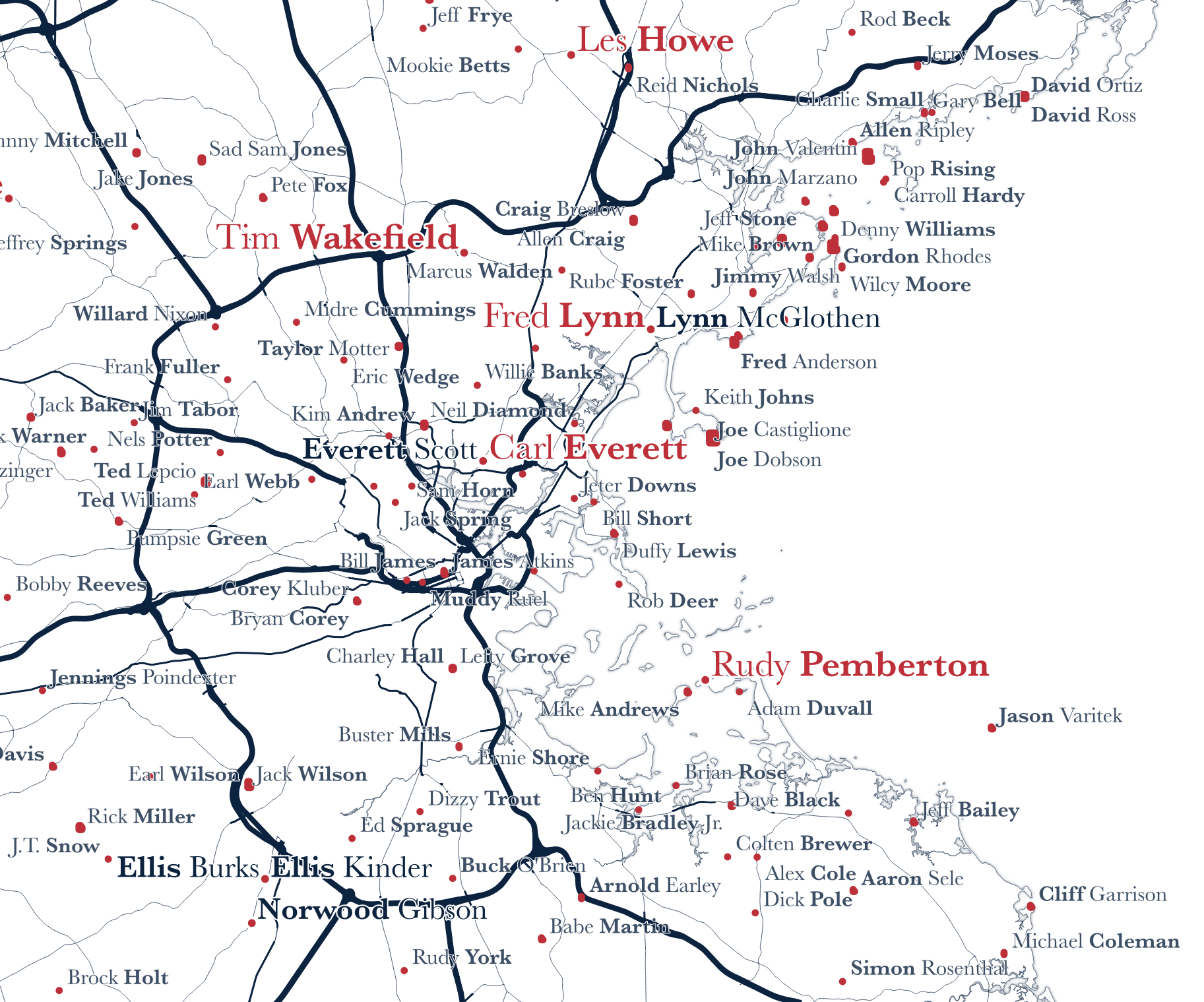

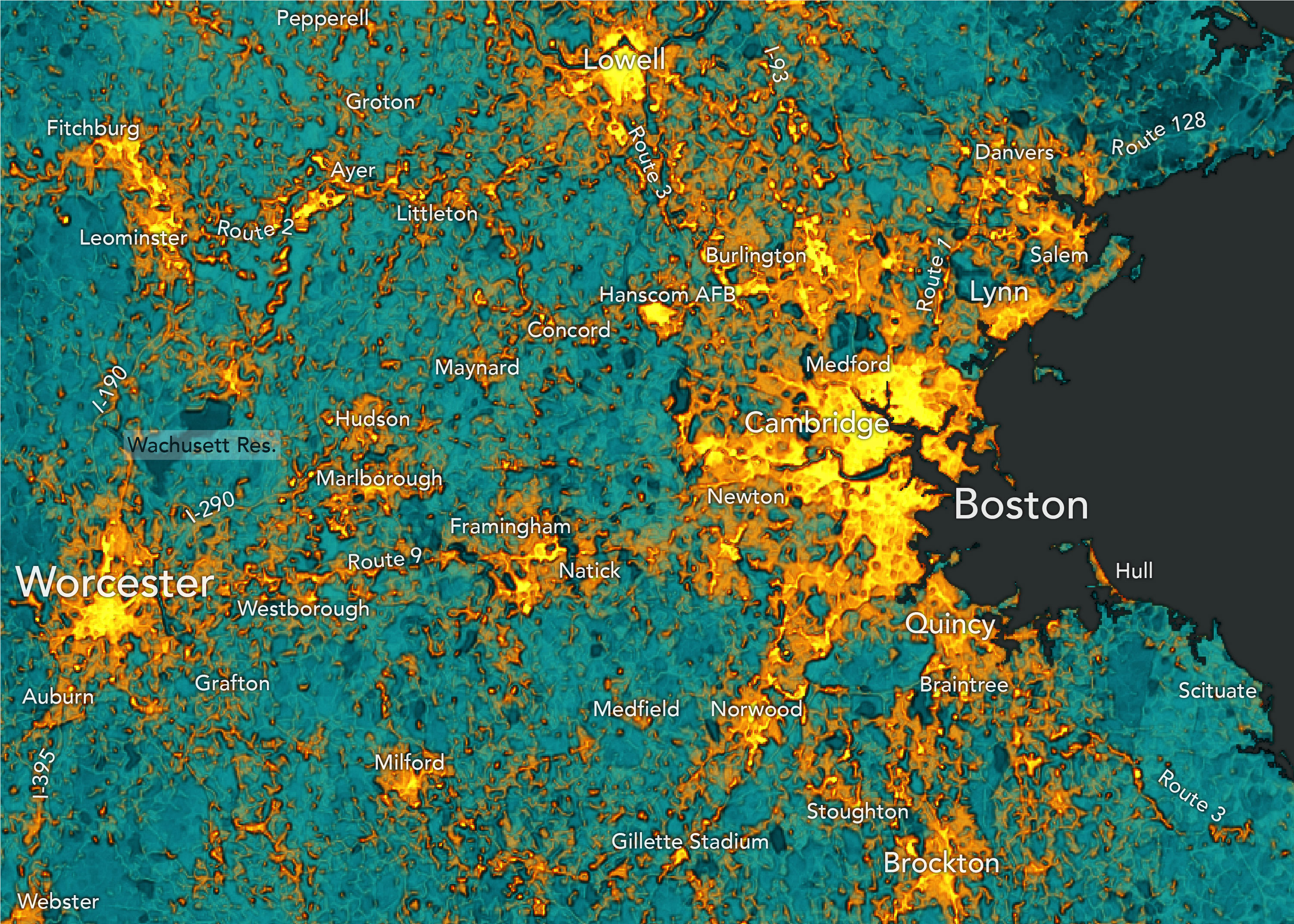

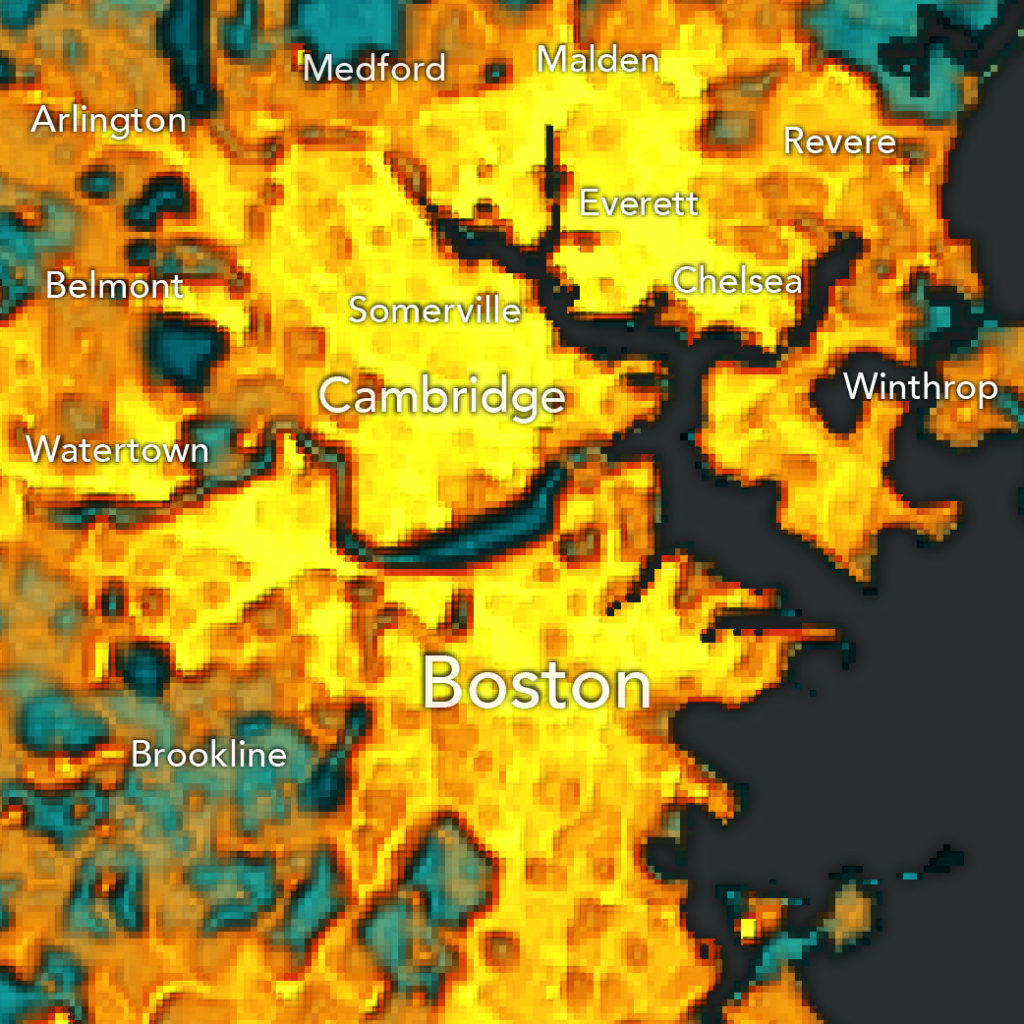

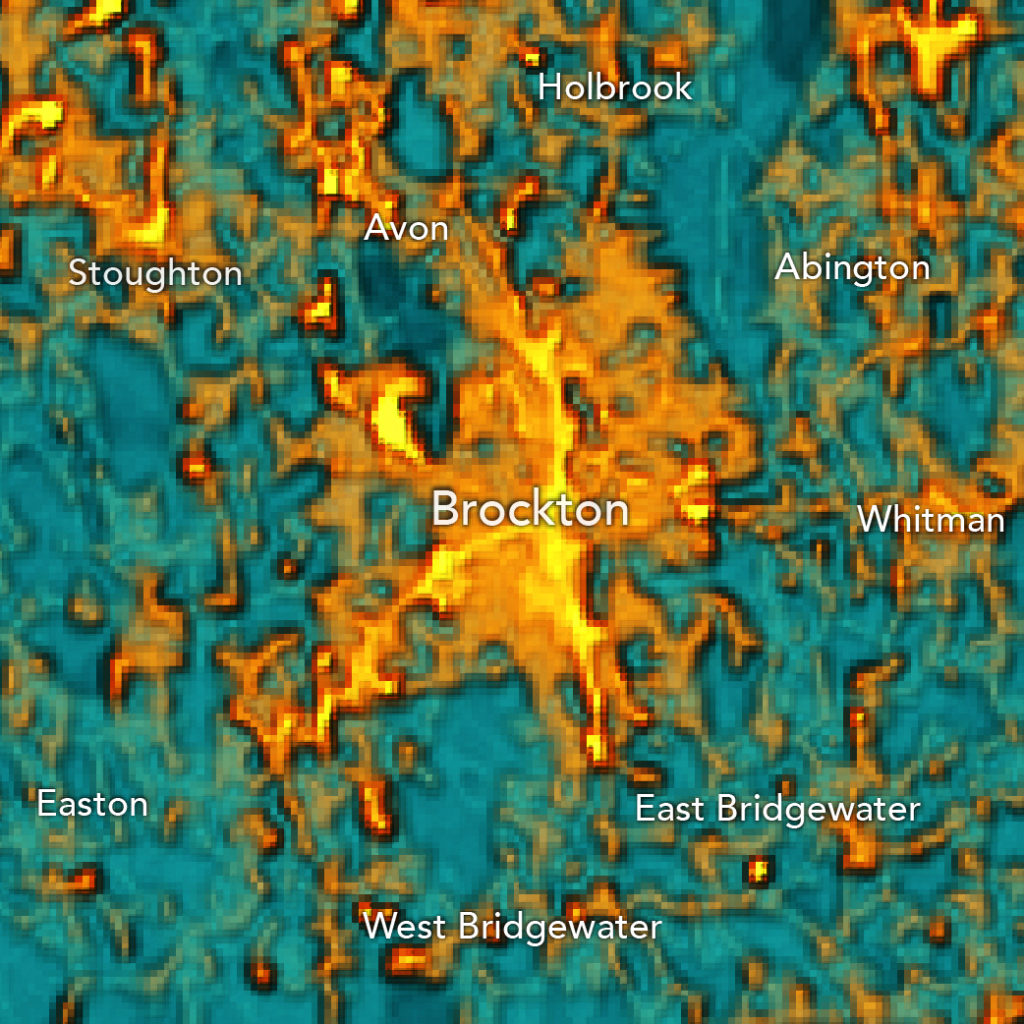

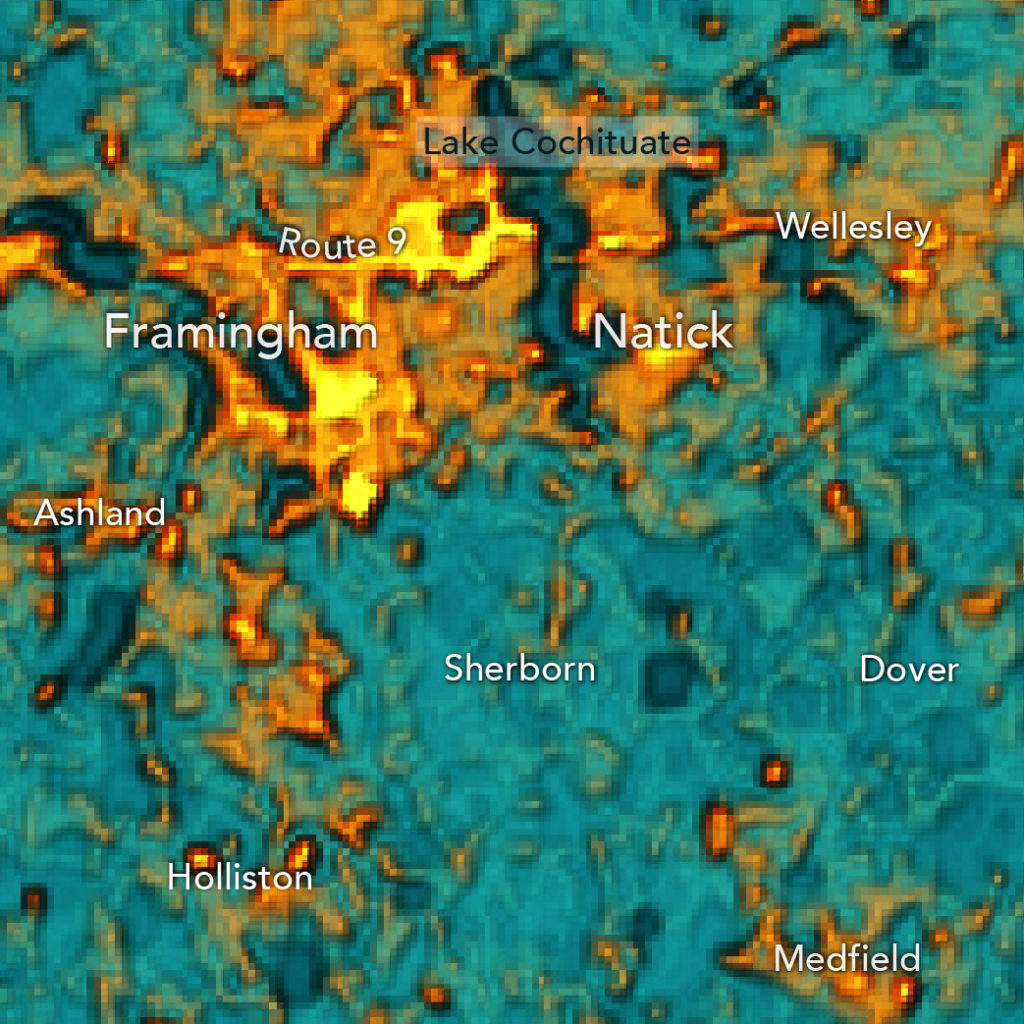

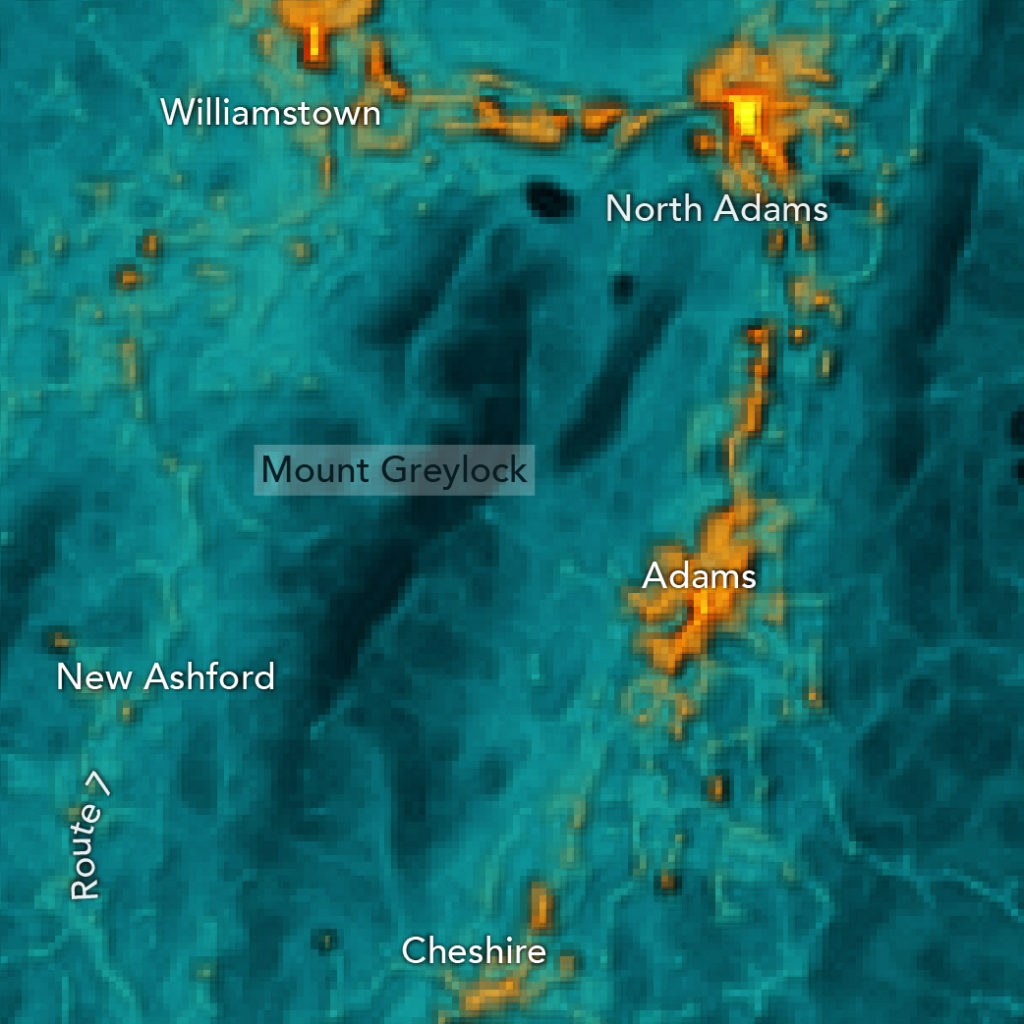

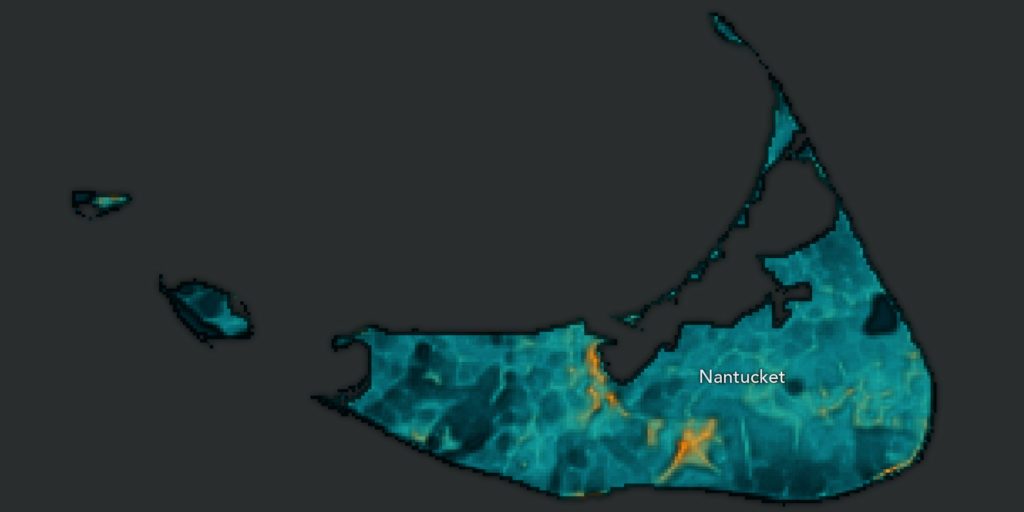

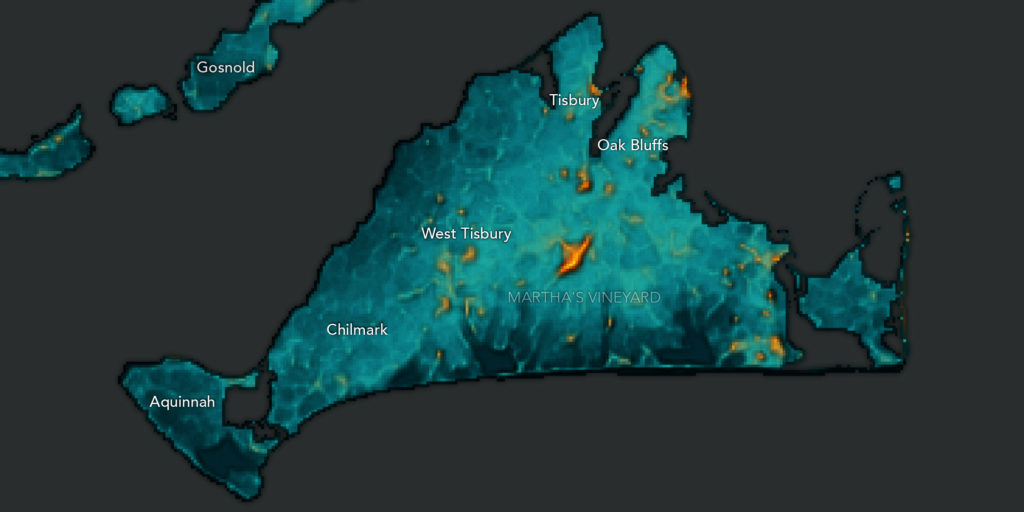

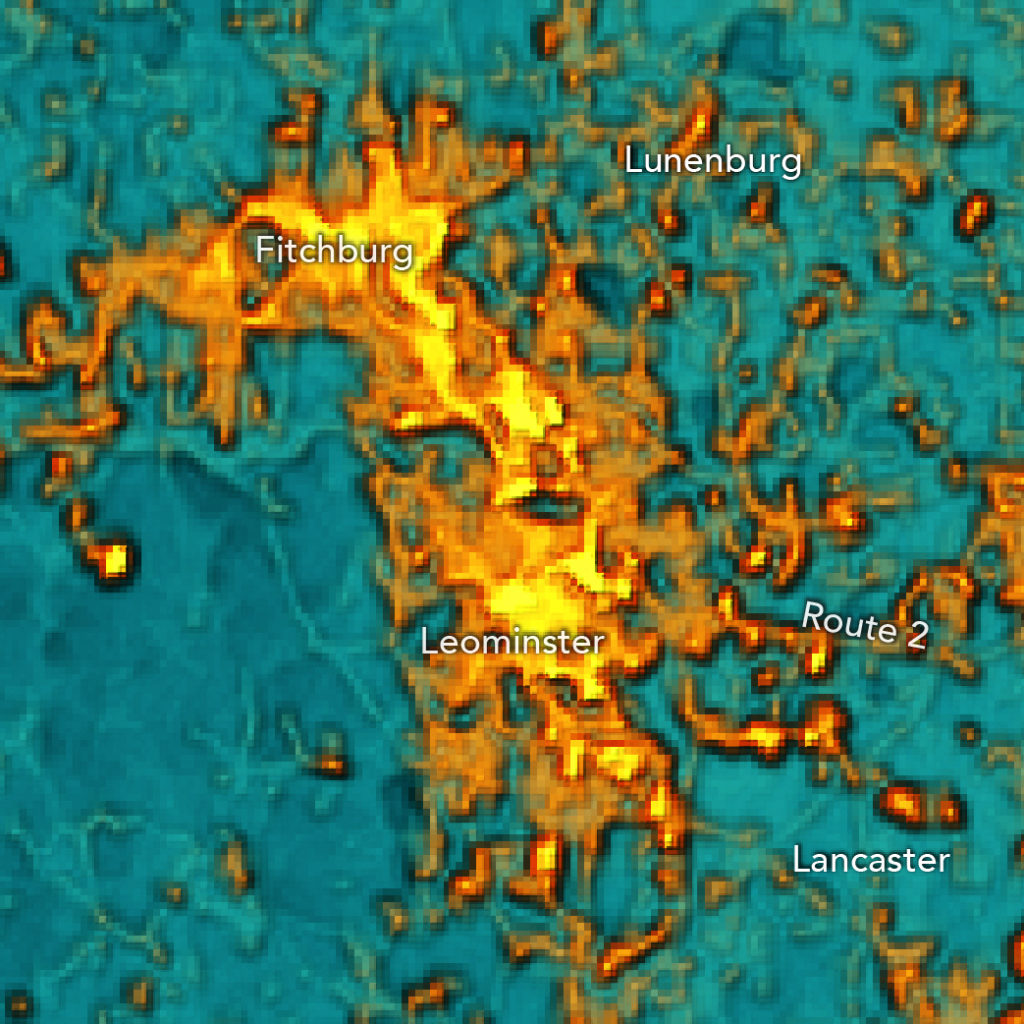

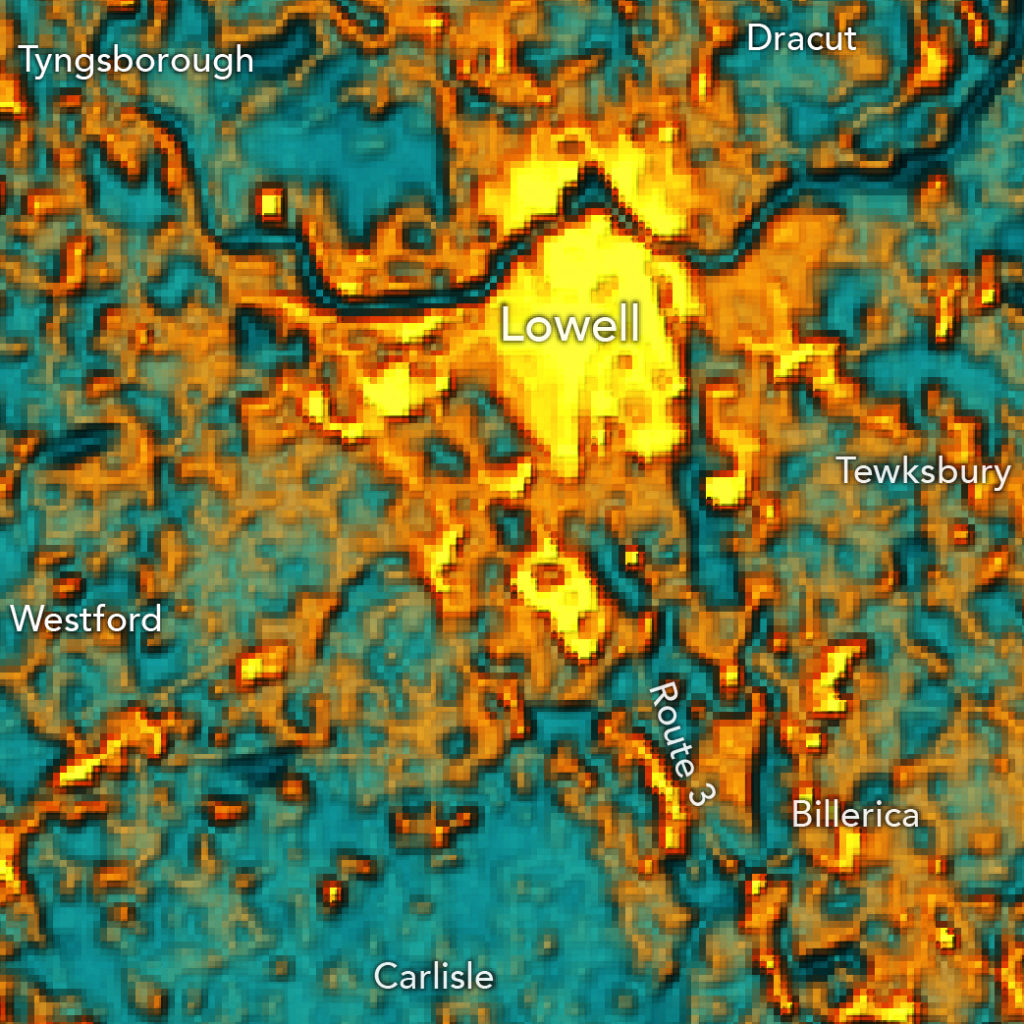

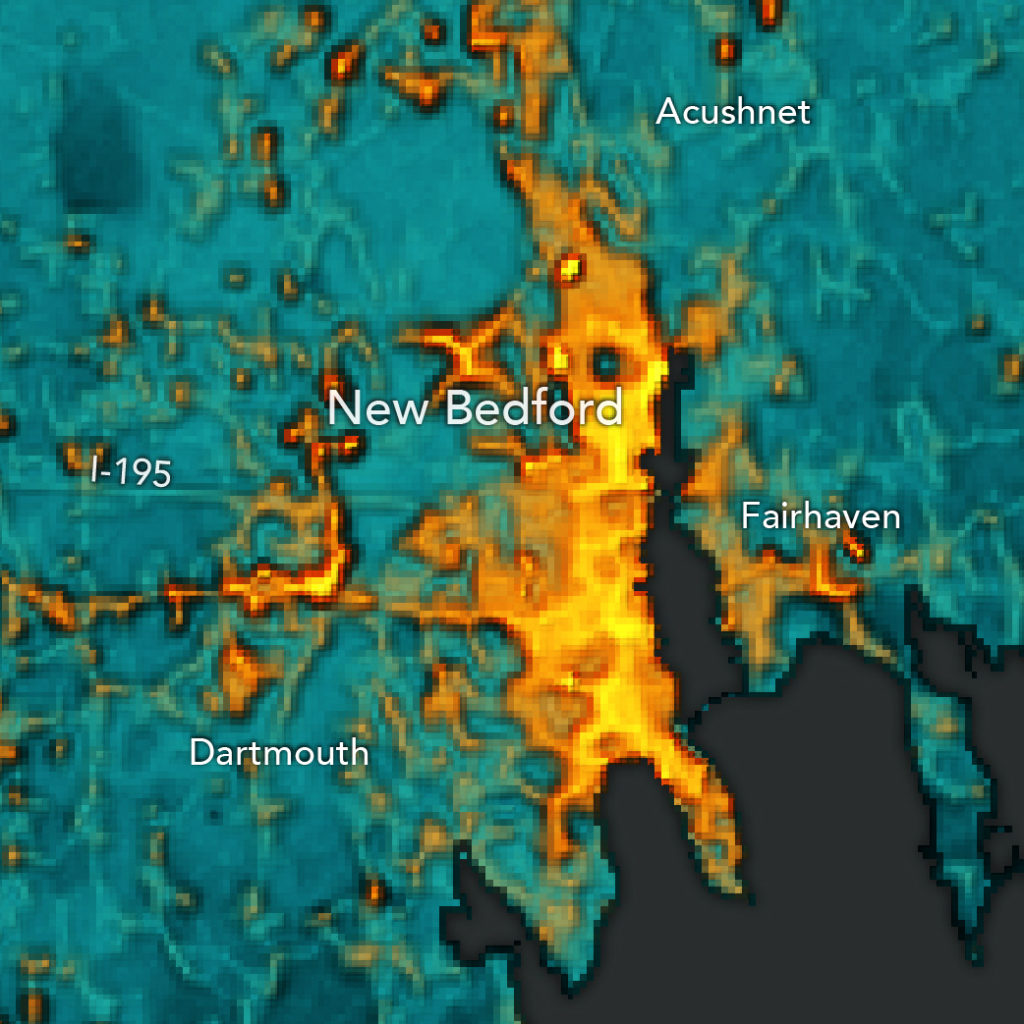

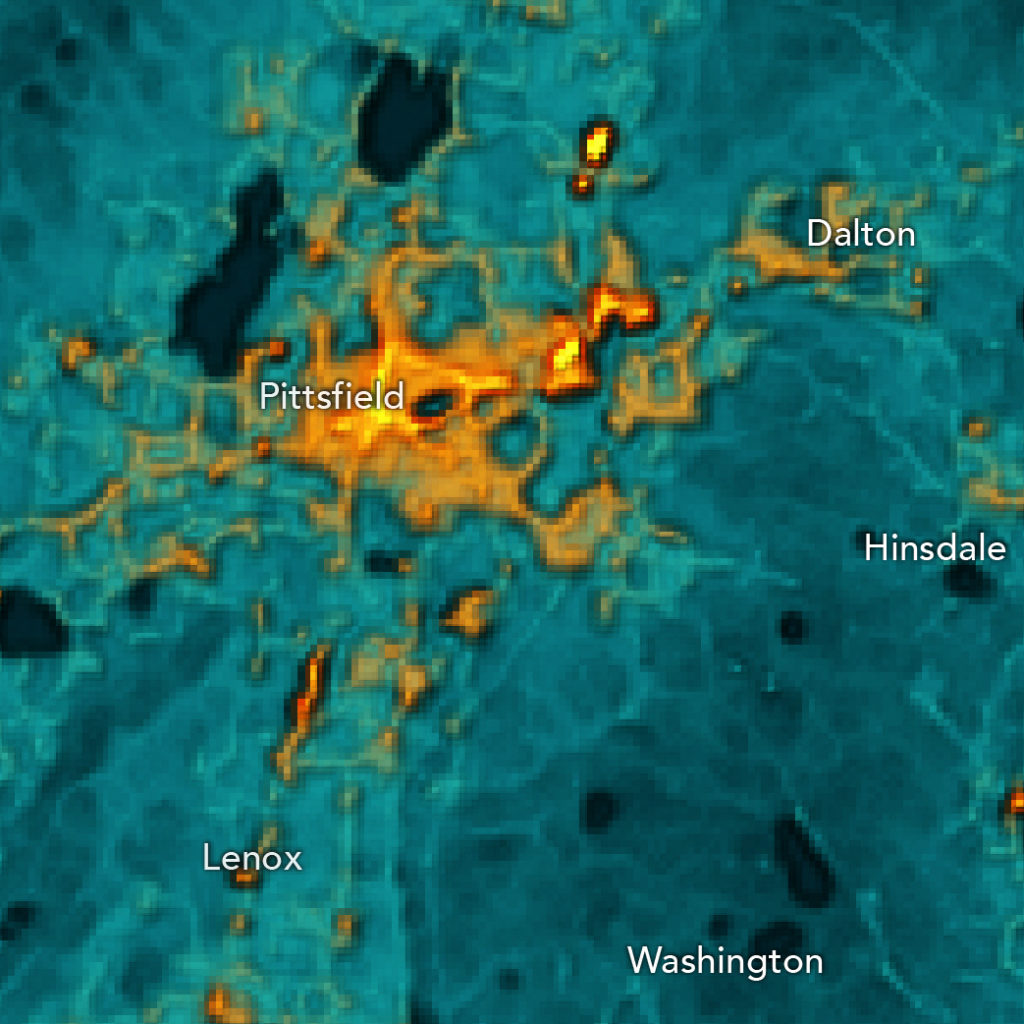

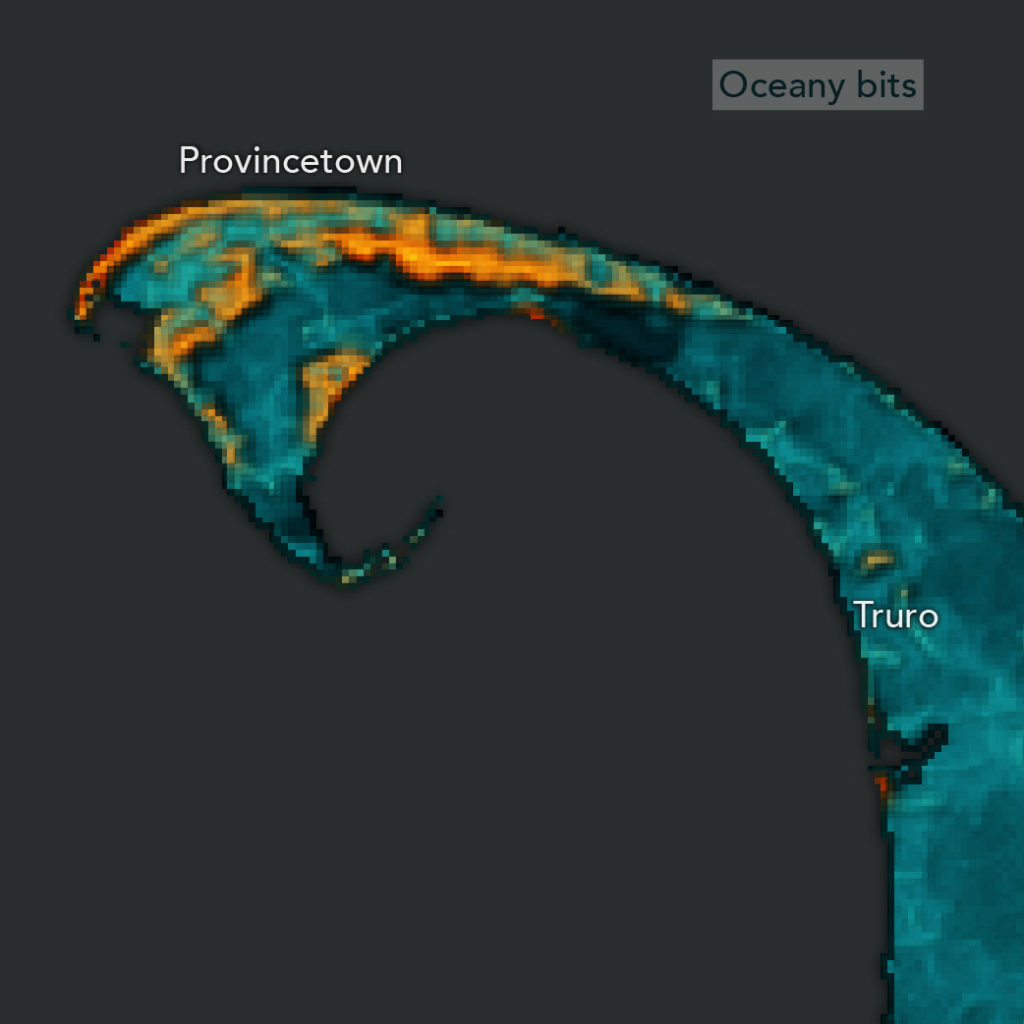

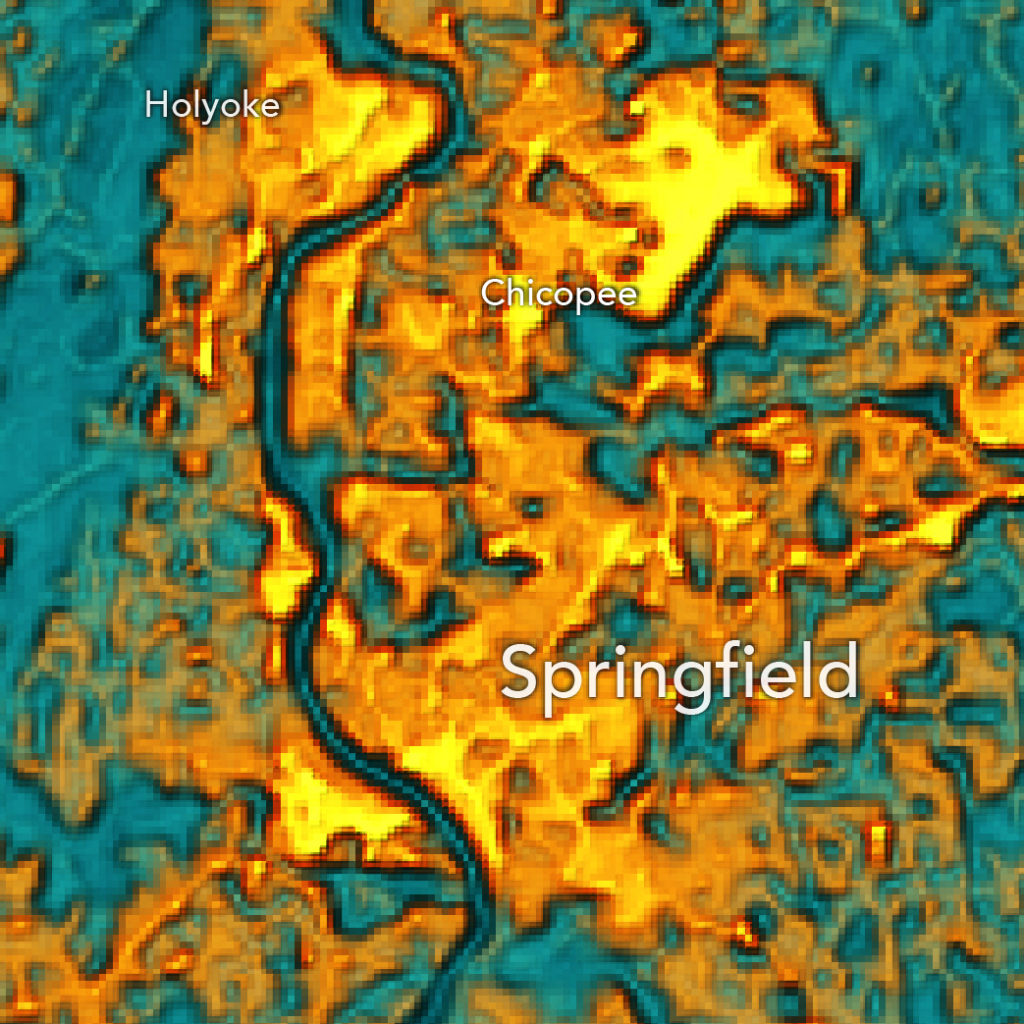

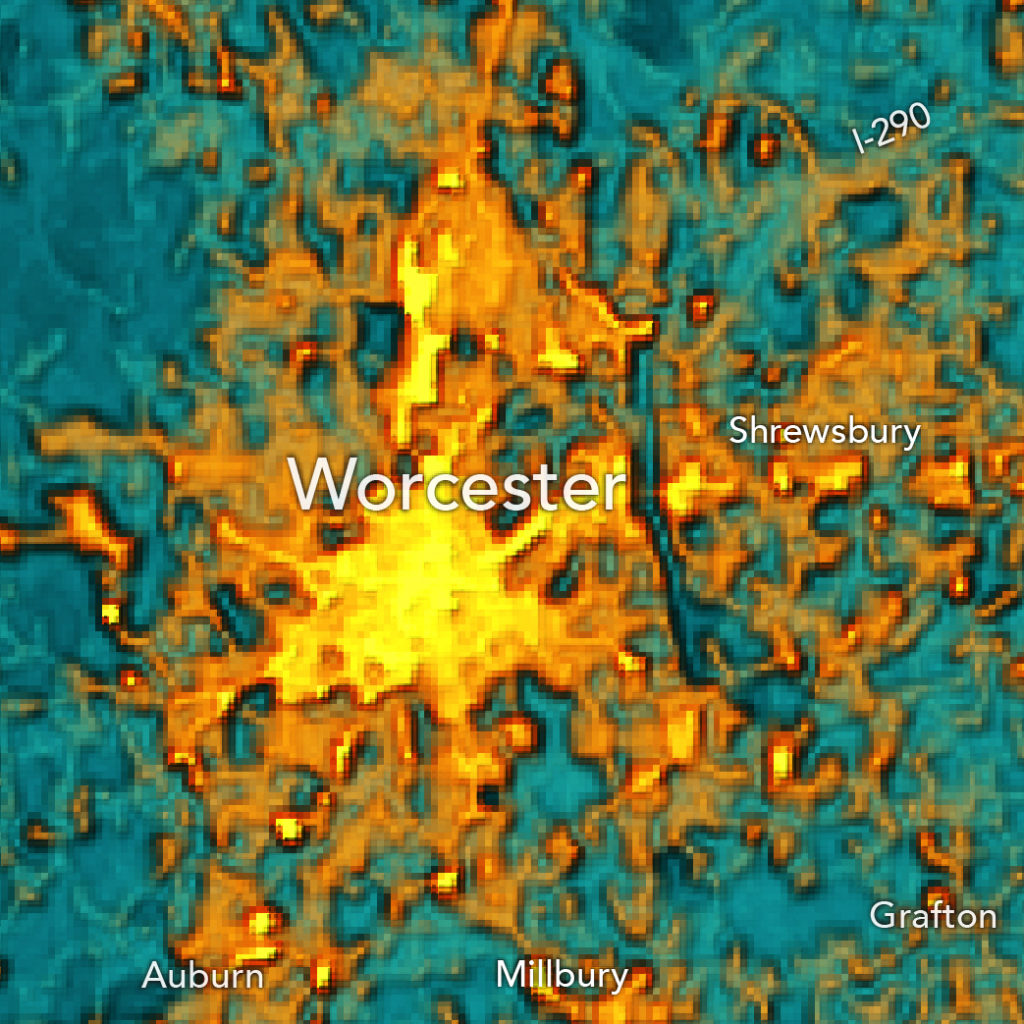

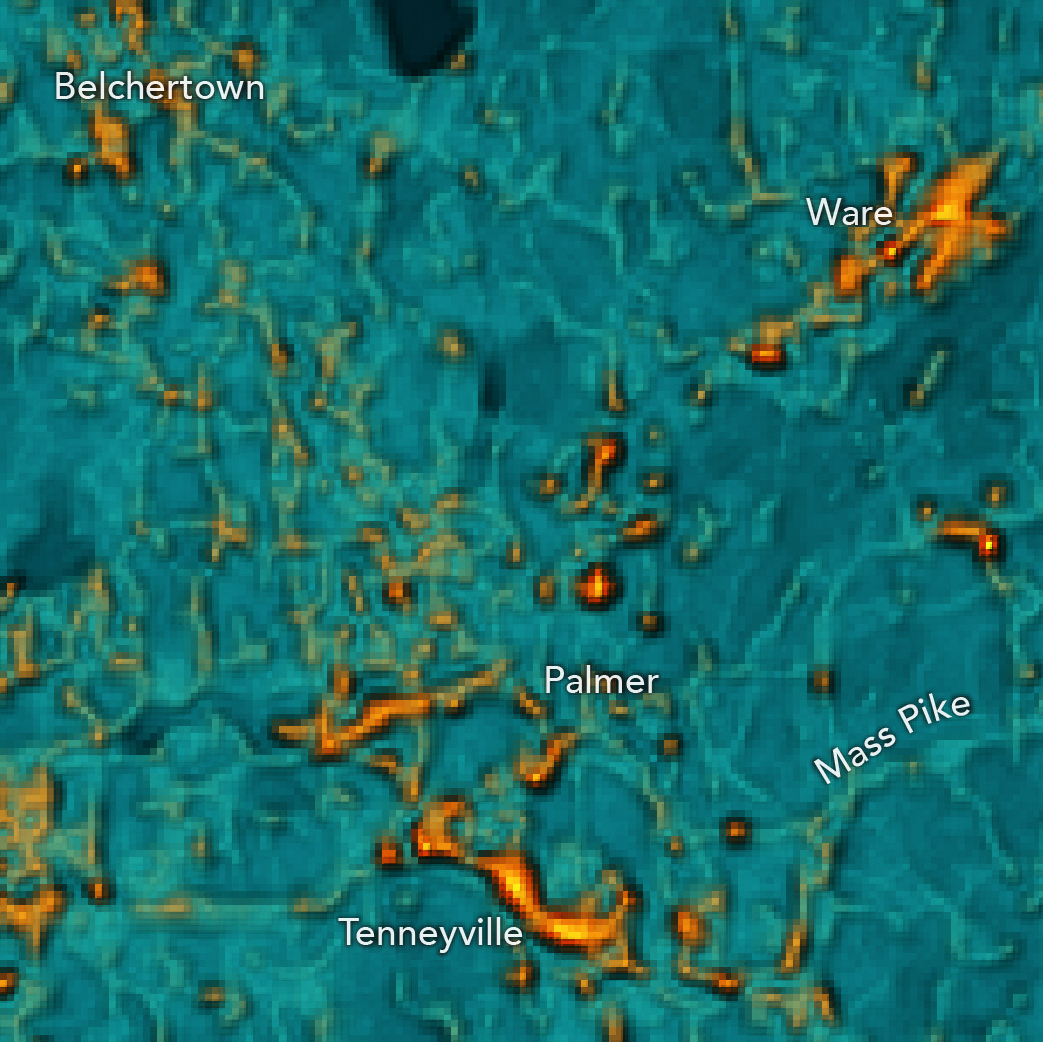

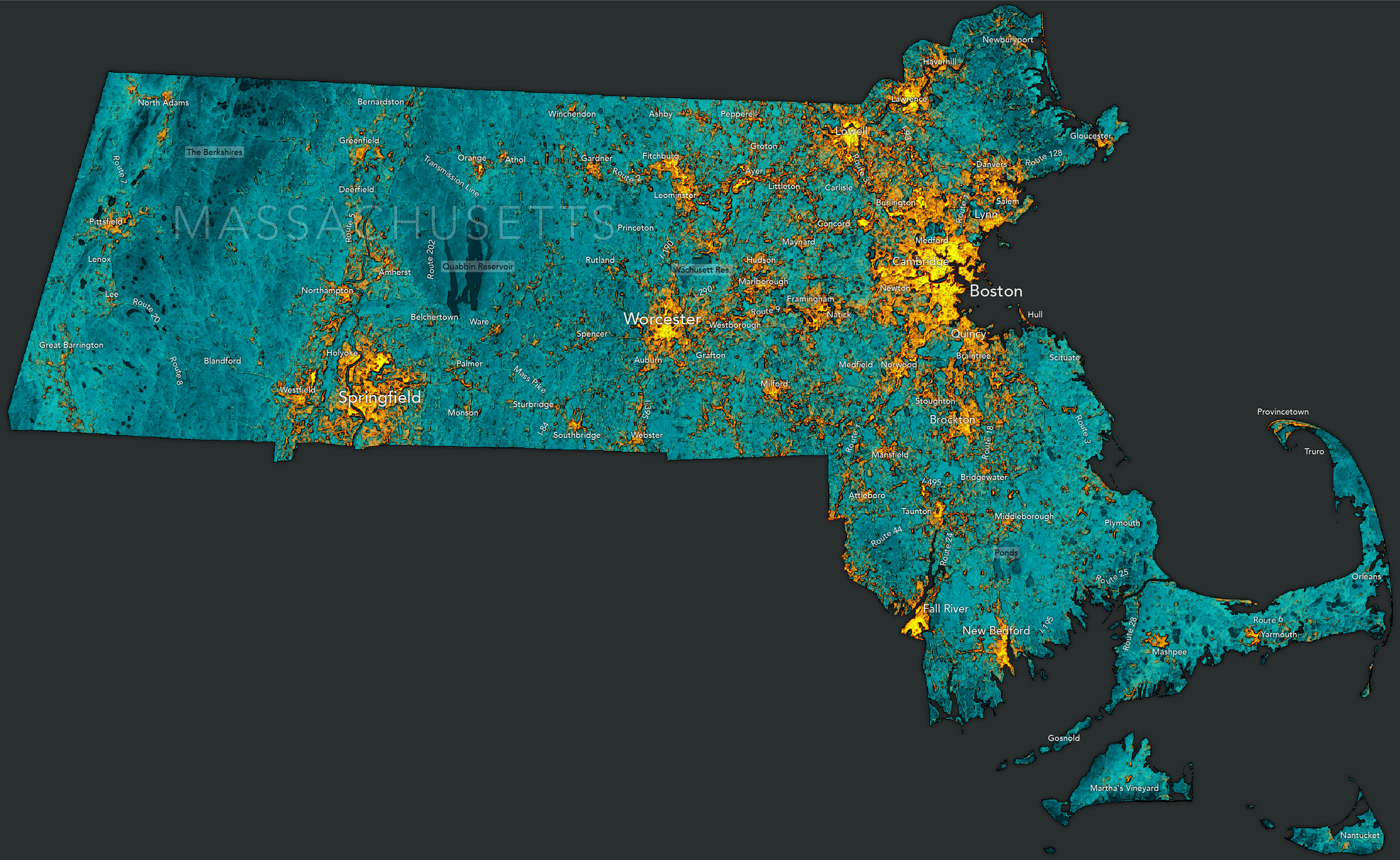

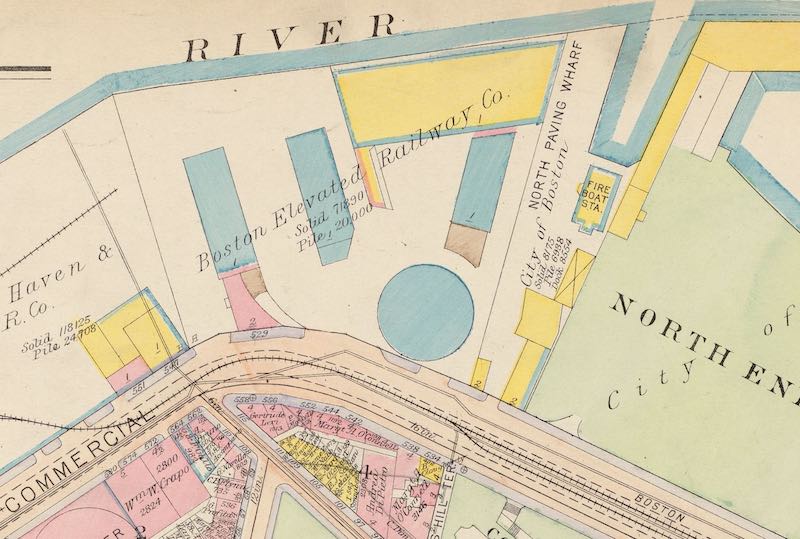

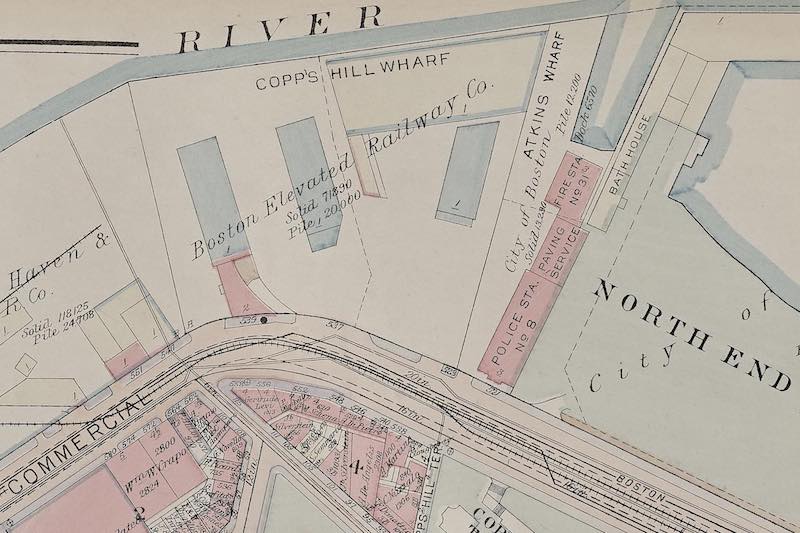

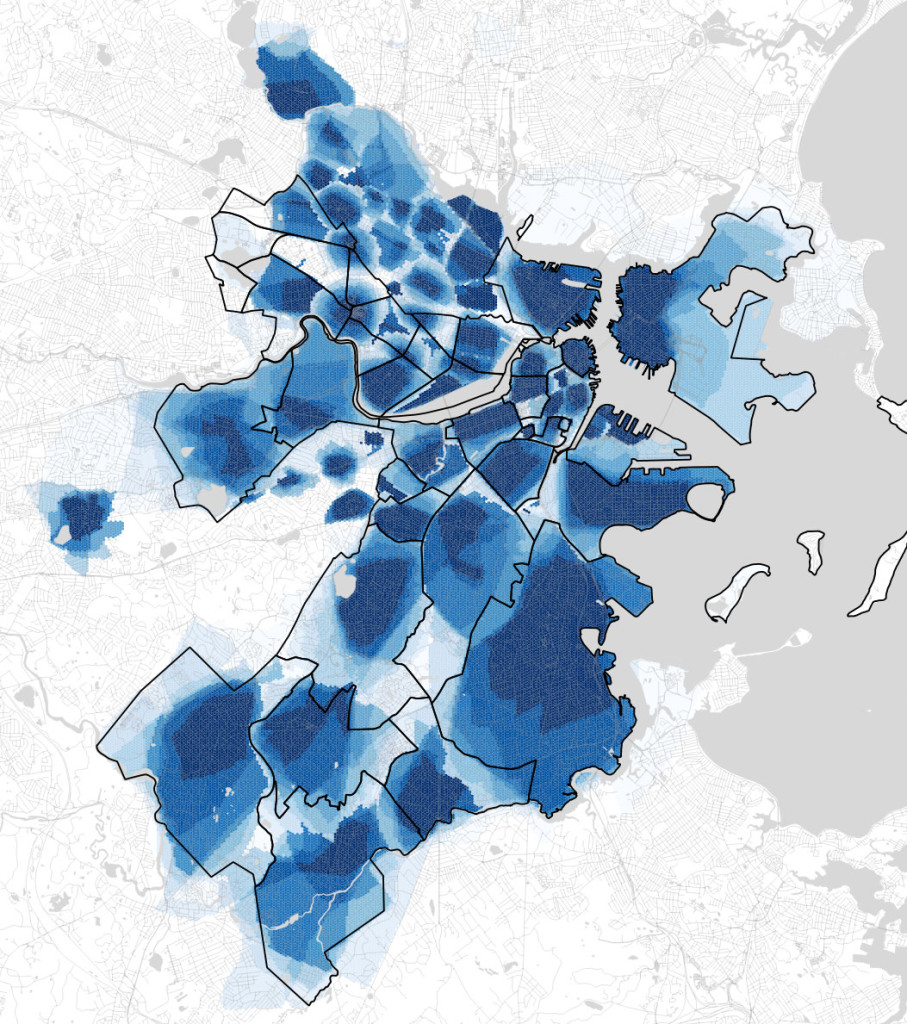

Inspired by this Ned.wtf blog post, a map of Red Sox, Massachusetts shows where 987 Red Sox players (pitchers and batters) from over the years share names with places and features in Massachusetts.

By my count, at least 53 Red Sox players share their last name with populated places in Massachusetts.

- Joe Harris, 1905-1907

- Walter Carlisle, 1908-1908

- Larry Gardner, 1908-1917

- Tubby Spencer, 1909-1909

- Allen Russell, 1919-1922

- Sam Dodge, 1921-1922

- Chick Maynard, 1922-1922

- Les Howe, 1923-1924

- Dud Lee, 1924-1926

- Bob Adams, 1925-1925

- Jack Russell, 1926-1936

- Bill Harris, 1938-1938

- Mickey Harris, 1940-1949

- Rip Russell, 1946-1947

- Fred Hatfield, 1950-1952

- Sid Hudson, 1952-1954

- Al Worthington, 1960-1960

- Ray Webster, 1960-1960

- Lou Clinton, 1960-1964

- Galen Cisco, 1961-1967

- Billy Gardner, 1962-1963

- Bill Lee, 1969-1978

- Bob Montgomery, 1970-1979

- Fred Lynn, 1974-1980

- Mike Paxton, 1977-1977

- Bob Stanley, 1977-1989

- Garry Hancock, 1978-1982

- Bob Watson, 1979-1979

- Wes Gardner, 1986-1990

- Tom Bolton, 1987-1992

- Greg Harris, 1989-1994

- Jeff Plympton, 1991-1991

- Jeff Russell, 1993-1994

- Andre Dawson, 1993-1994

- Erik Hanson, 1995-1995

- Joe Hudson, 1995-1997

- Reggie Jefferson, 1995-1999

- Tim Wakefield, 1995-2011

- Reggie Harris, 1996-1996

- Rudy Pemberton, 1996-1997

- Mike Stanley, 1996-2000

- Lenny Webster, 1999-1999

- Sang-Hoon Lee, 2000-2000

- Carl Everett, 2000-2001

- Josh Hancock, 2002-2002

- Terry Adams, 2004-2004

- Chad Bradford, 2005-2005

- Willie Harris, 2006-2006

- Mike Lowell, 2006-2010

- Royce Clayton, 2007-2007

- Drew Sutton, 2011-2011

- Allen Webster, 2013-2014

- James Paxton, 2023-2023

At least 23 players share their first name with a populated place in Massachusetts.

- Tully Sparks, 1902-1902

- Norwood Gibson, 1903-1906

- Everett Scott, 1914-1921

- Otis Miller, 1930-1932

- Lee Rogers, 1938-1938

- Ellis Kinder, 1948-1955

- Lee Thomas, 1964-1965

- Dalton Jones, 1964-1969

- Dennis Bennett, 1965-1967

- Lee Stange, 1966-1970

- Lynn McGlothen, 1972-1973

- Dwight Evans, 1972-1990

- Dennis Eckersley HOF, 1978-1998

- Lee Graham, 1983-1983

- Ellis Burks, 1987-2004

- Lee Smith HOF, 1988-1990

- Dennis Lamp, 1988-1991

- Otis Nixon, 1994-1994

- Lee Tinsley, 1994-1996

- Paxton Crawford, 2000-2001

- Franklin Morales, 2011-2013

- Clayton Mortensen, 2012-2013

- Heath Hembree, 2014-2020

Some 229 players share part of their name with part of a populated place name. Wally the Green Monster, for instance, shares part of his name with The Green in Middleboro. I won’t list them all here. Rest assured it’s a group of many Toms, Bobs and Teds.

The remaining player names match to other geographic features that include summits, lakes, islands, reservoirs, streams, bars (coastal, not sports), bays, capes, and swamps.

To explore them all, check out this Felt Map. And, as ever, go Sox.

—

I welcome corrections, additions and heckles. This map is silly more than anything else, and there is no objective right or wrong way to make it. But for those of you who are interested, a few notes on my methodology for this version:

-

- Place names were drawn from GNIS. Aggregating with better sources for local place names would be fun. I did not do that here.

- Player names and years were drawn from Baseball Reference. I know that Ellis Burks didn’t play for the Red Sox for 17 straight years, but this is how the source lists his tenure on the team roster.

- Player names were matched to place names in order of priority: last name to full-place-name matches were the highest priority, followed by first name to full-place name, and so on. Where there were multiple places that matched players’ names, the closest place to Fenway was used.

- Mapping across all of Red Sox Nation would be an improvement.

- Of course I also did this for every other active franchise.

- Yep, I also did this for this year’s All-Stars.