UPDATE! We’ve got a new and better version of the neighborhood mapping project! Head on over to bostonography.com/hoods!

OLDER UPDATE: There’s also a newer map of what’s described below.

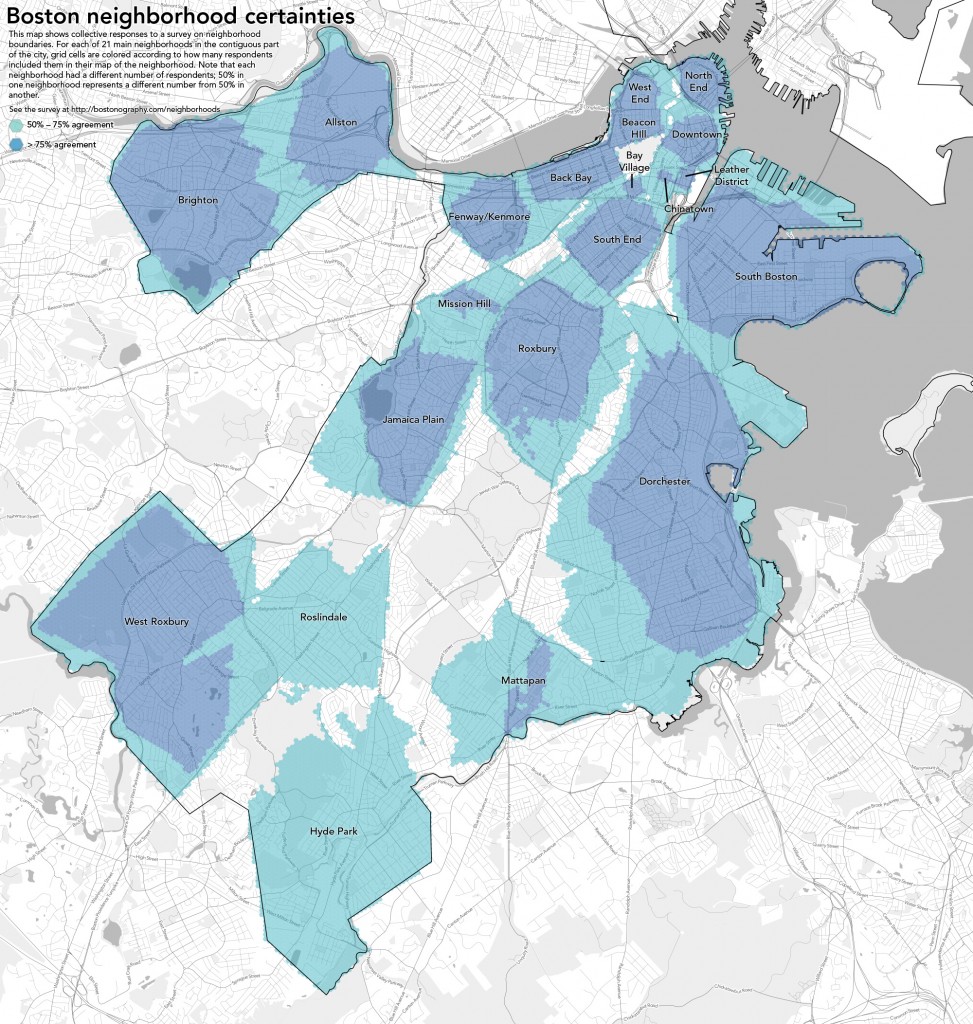

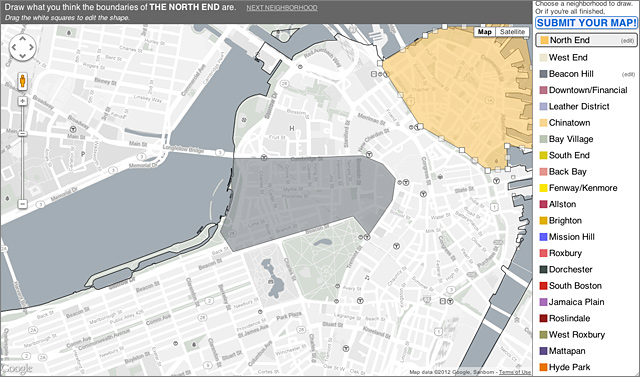

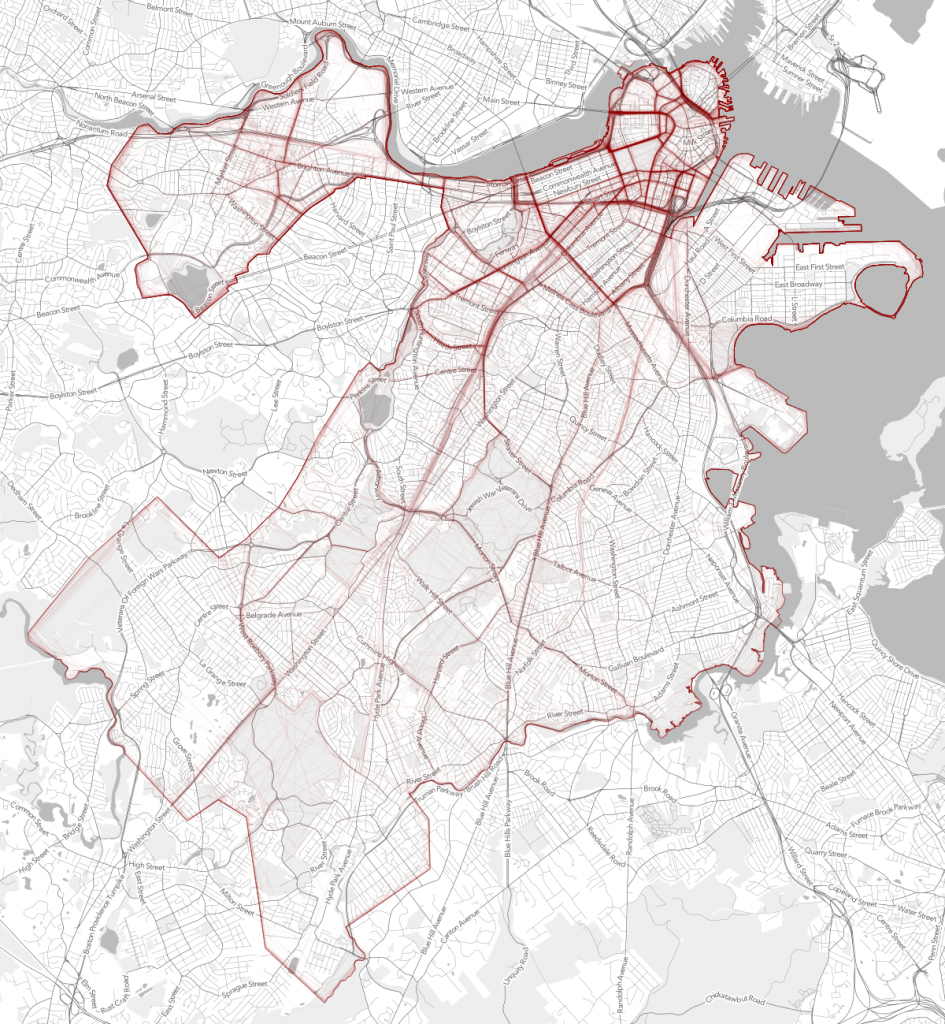

As you may recall, we’re running an ongoing project soliciting opinions on Boston’s neighborhood boundaries via an interactive map. We want to keep collecting data, but we’ve already received excellent responses that we’re itching to start mapping, and when we hit 300 submissions recently it seemed like a good enough milestone to take a crack at it. (That’s actually 300 minus some junk data. If you offer the ability to draw freeform shapes, some people draw random rectangles and triangles, and some people draw… er, other long, tipped objects.)

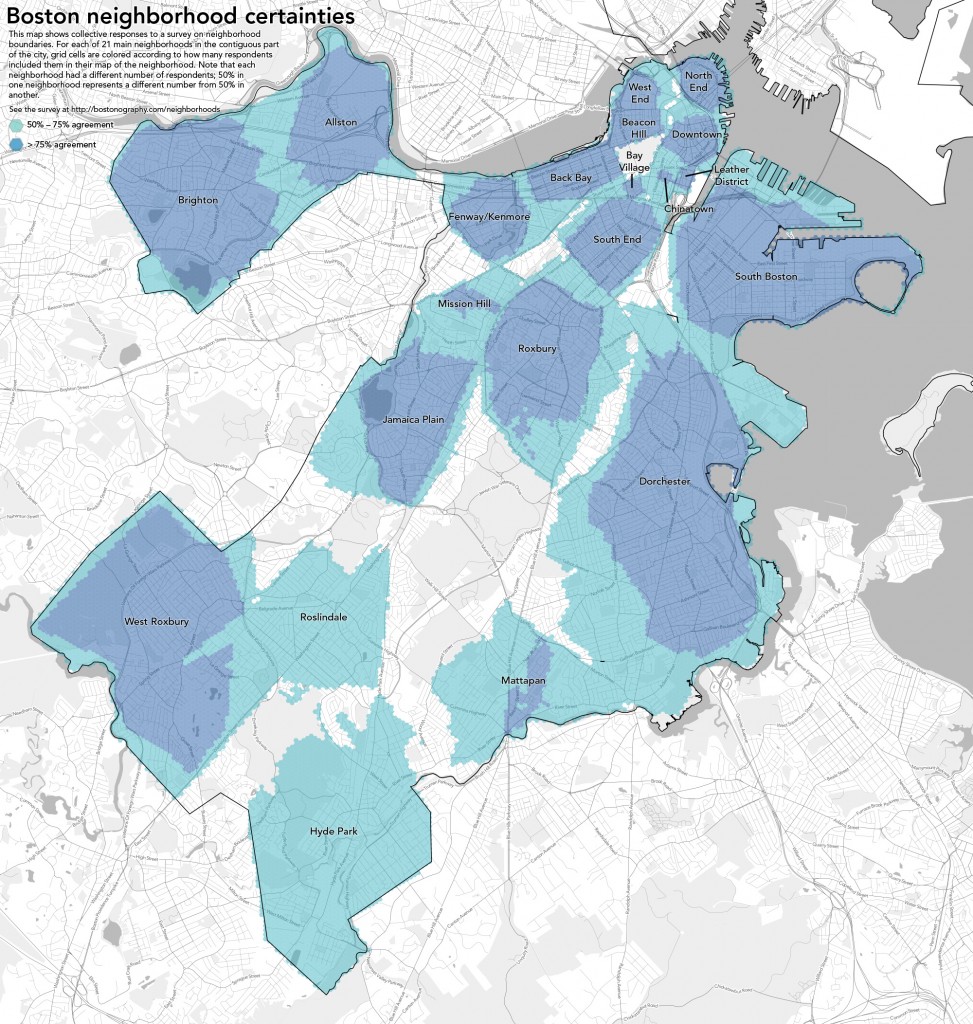

There are many questions to be asked here. Where are the areas of consensus? Where are the disputed zones? Where are the no-man’s lands? &c.? Let’s tackle these one at a time in a series of posts and maps. Today we look at consensus.

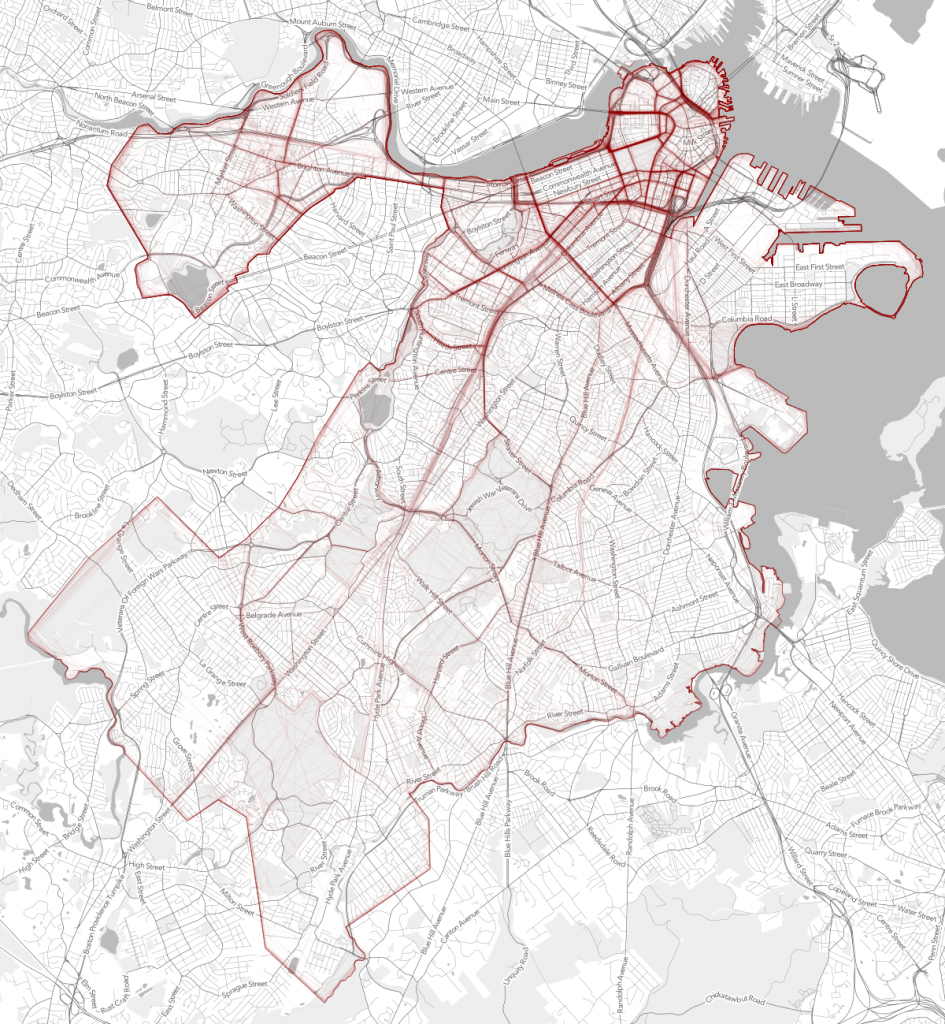

But first, let’s check out a raw picture of the boundaries everyone has drawn. This map, which is clipped to the city limits, shows that the word “tangled” is apt in reference to neighborhood boundaries. Some lines are strong as a result of many people drawing in the same place, but many others are all over the place.

Based on those strong lines we can kind of see where there is decent agreement on boundaries, but we can quantify this for all of the neighborhood extents. What we have is 21 sets of polygons, each set representing the shapes people drew for one of the neighborhoods in our survey (the main neighborhoods except for the physically isolated Charlestown and East Boston). Within the set for each neighborhood we can look at the amount of overlap between polygons and consider overlapping areas to be areas of agreement between two or more respondents—as many respondents as there are overlapping polygons in that area. In this exercise we’re interested in those counts. We could find the area in which all polygons overlap, for instance, which would represent the area that 100% of people agree is part of the neighborhood. Total consensus usually doesn’t show us much or doesn’t exist, though, because of some especially bad data (some people just didn’t have a clue, although we tried to weed those out) and, well, because definitive agreement probably is impossible anyway. But we can still find the areas where there is moderate to strong agreement—at least among the self-selected people who responded to the survey.

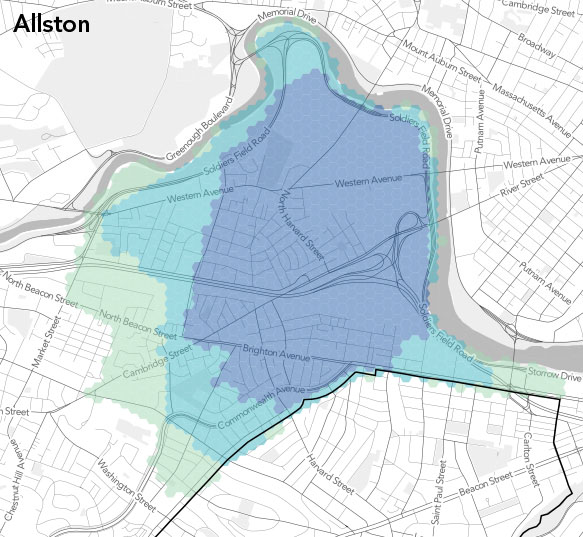

We’ve chosen to look at areas of greater than 25% agreement, greater than 50%, and greater than 75%. They’re handy numbers that seem represent a notable minority, a majority, and a strong majority. So let’s get to the maps. We’ve laid down an arbitrary hexagonal grid across the city and for each cell tallied how many respondents’ polygons it intersects in each neighborhood, then divided that count by the total number of respondents for the neighborhood, which ranged from a little over 40 to 150ish. Here, then, are the neighborhoods in almost alphabetical order, with the number of submissions noted for each.

(Note: when we started these, hexagons had slightly more carto-hipster cachet. These are not really the hexagonal bins that have been recently popular—albeit legitimately useful—but rather kind of a coarse raster approach that looks nicer than squares.)

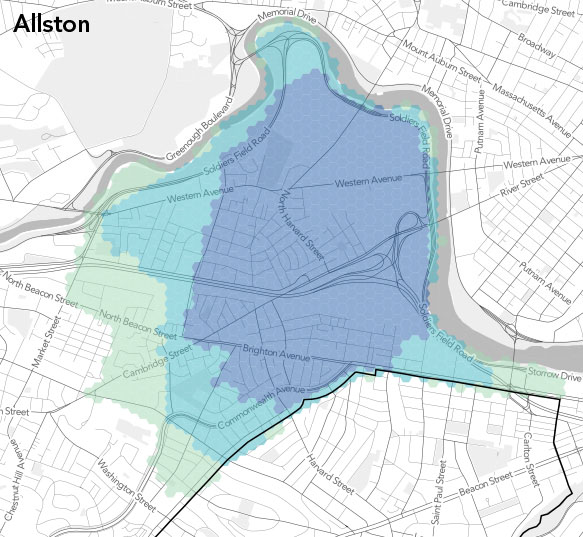

Allston (n=120). The first map, I think, demonstrates how closely the categories tend to follow certain streets in all the neighborhoods. Market Street and Everett Street mark the western edges of the 25% and 75% categories, respectively, with 50% a little less defined on that side. Each level then cuts east and south in a couple of steps. It’s interesting that the commercial center of Allston, the Harvard Ave corridor, is only barely within the area of strongest agreement. A neighborhood “center” isn’t always in the middle!

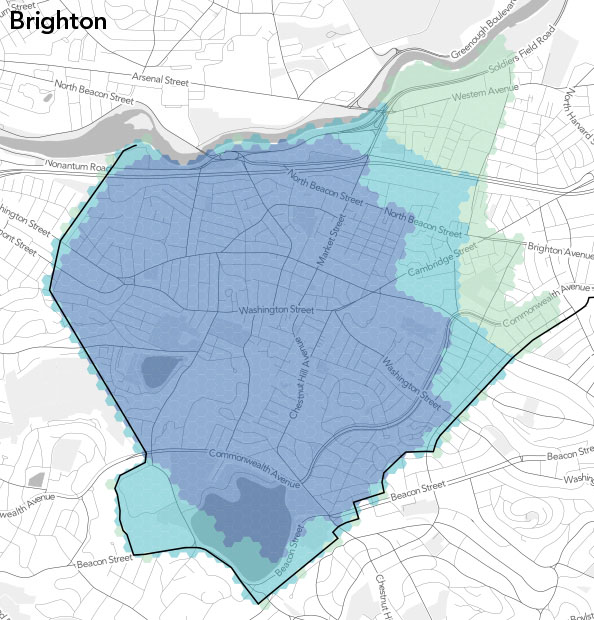

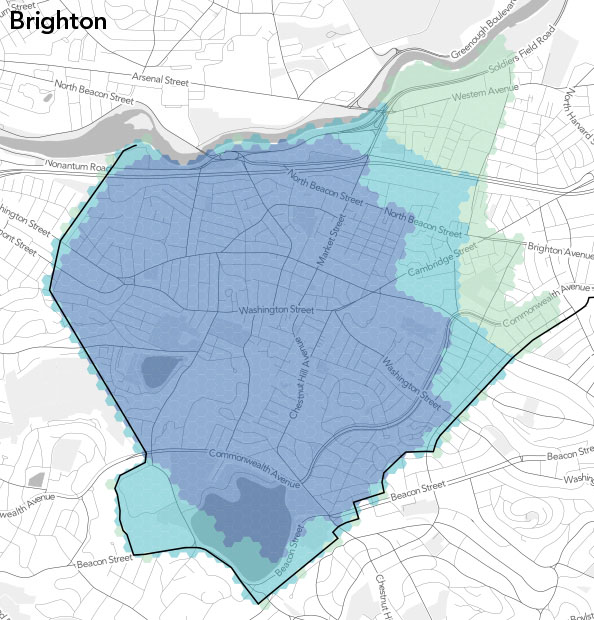

Brighton (n=109). Not surprisingly, Brighton’s eastern edge matches up fairly well with Allston’s western edge. They’re not exactly interlocking jigsaw puzzle pieces, however, because not everyone who drew one neighborhood drew the other, nor were they necessarily careful to make the borders match precisely.

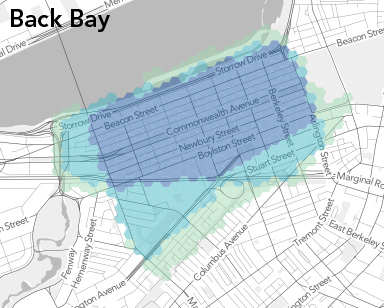

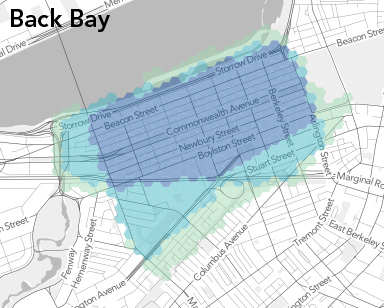

Back Bay (n=139). There are some hard lines here. Nobody goes past the Charlesgate, or past Mass Ave south of the Pike. An interesting section is that south of Huntington Ave. It has the character of the South End but Back Bay parking permits, presumably because the Southwest Corridor partially cuts it off from the former. Still, it doesn’t enjoy majority Back Bay status in this map.

Bay Village (n=80). Not much room to mess around in this tiny neighborhood. The majority stays south of Stuart Street, with the supermajority between Arlington and Charles. The part north of Stuart, although small relative to the whole city, will be interesting to look at later as a no-man’s land; it seems hard to classify even though it has decent Bay Village representation here.

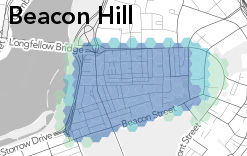

Beacon Hill (n=145). This may be the neighborhood with the most consensus. Everyone agrees on the southern, western, and northern boundaries. On the east side, the question is only whether Bowdoin, Somerset, or Cambridge/Tremont Street is the edge.

Chinatown (n=113). It’s a little surprising how small the greatest agreement is here, at least to me. I’d probably draw something like the 50% shape. Note that even the Chinatown gate is just outside the 75% region. Perhaps it’s just hard to know which street is which on a map of this dense area, leading to more uncertain shapes from our respondents.

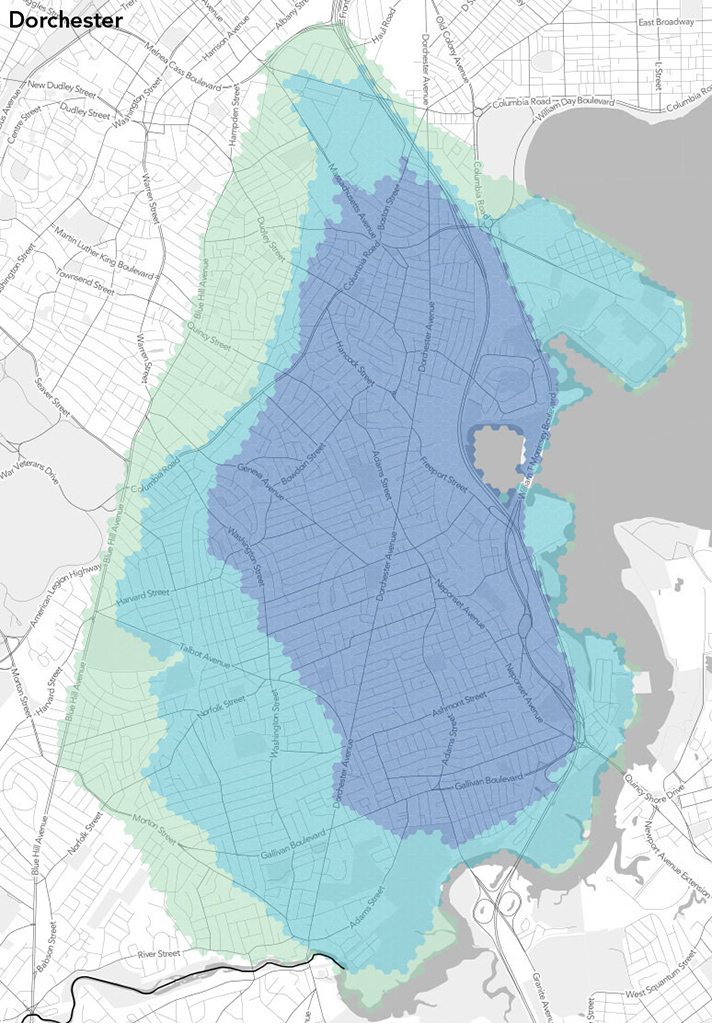

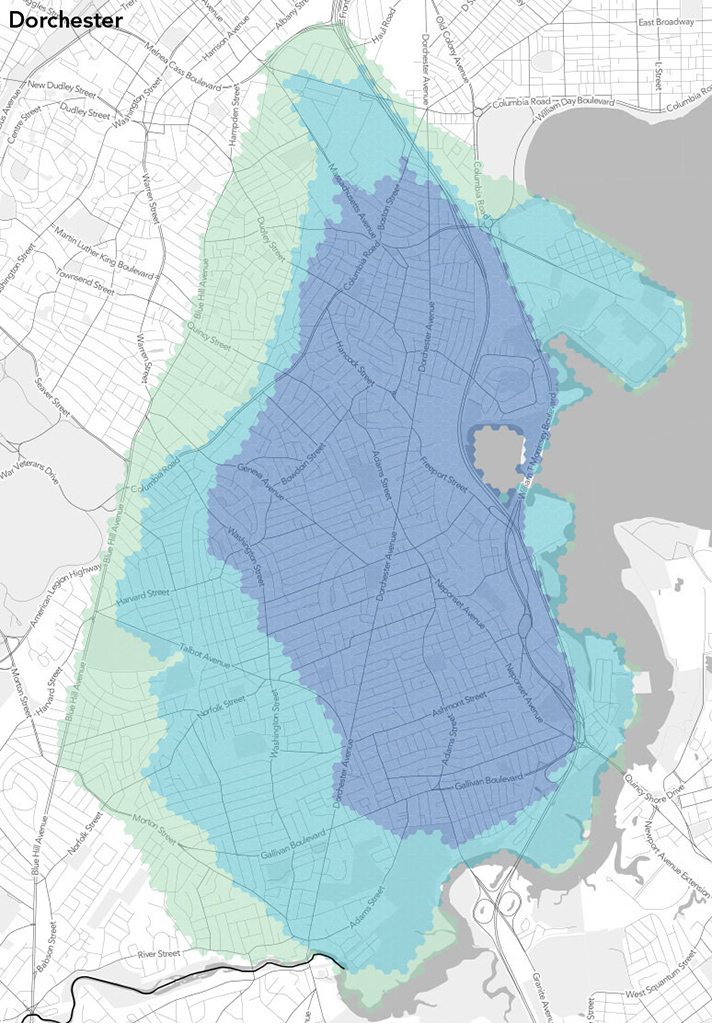

Dorchester (n=54). Dorchester is large enough that we probably need more responses in order to see more agreement. (This is the most populous neighborhood, of course, but it doesn’t have as many responses as some others, probably in part because it’s harder for non-residents to grasp.) Still, we have some good edges here: Blue Hill Ave for 25% and the Fairmount line for 50%. We’ll see those again in the Roxbury map.

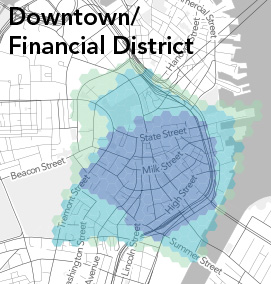

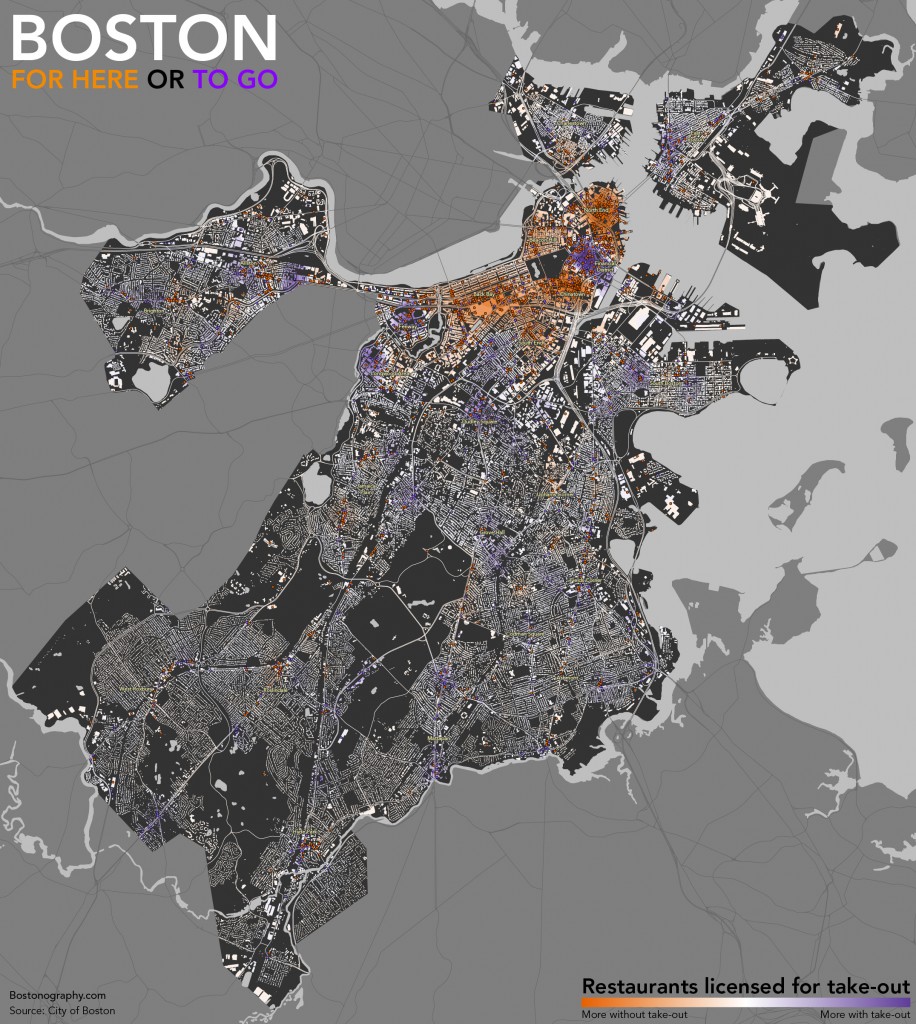

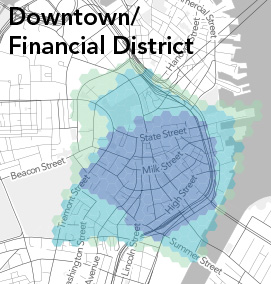

Downtown/Financial District (n=118). “Downtown” is fun to try to define, but we’ve wrapped it up here, perhaps not entirely appropriately, with the Financial District. Besides the easier-to-locate Financial District, to some degree this looks like a process-of-elimination neighborhood: if it isn’t Chinatown, the North End, &c., it must be downtown. Maybe that’s because it’s least residential neighborhood of the bunch, so there’s not really a strong identity.

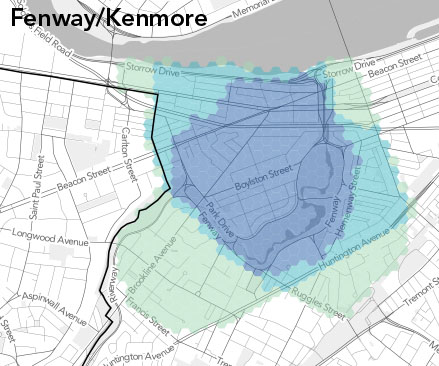

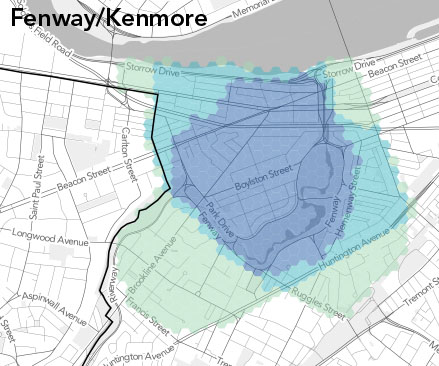

Fenway/Kenmore (n=128). I’m a bit surprised by how many people consider the Fenway neighborhood to end, well, at the Fenway itself on the west side. A minority of respondents here consider some of the Colleges of the Fenway to be actually in the neighborhood. What they’re thinking, presumably, is that this is the Longwood Medical Area and that the LMA is not part of the Fenway. It’s an intriguing zone because we left it off our neighborhood list, forcing people either to include it in an adjacent neighborhood or leave it blank. But we can talk more about that in another post.

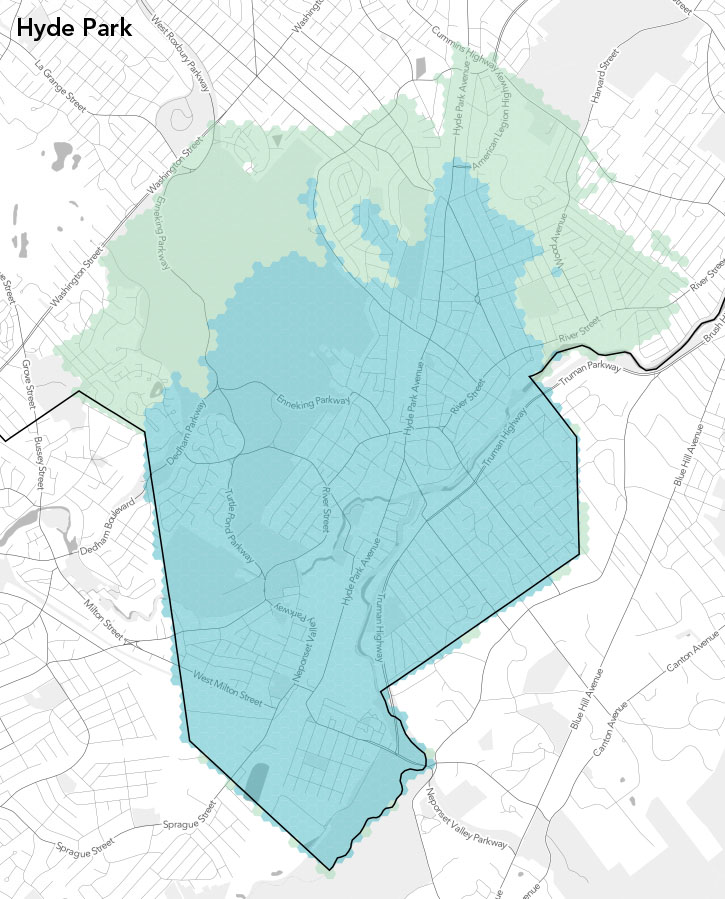

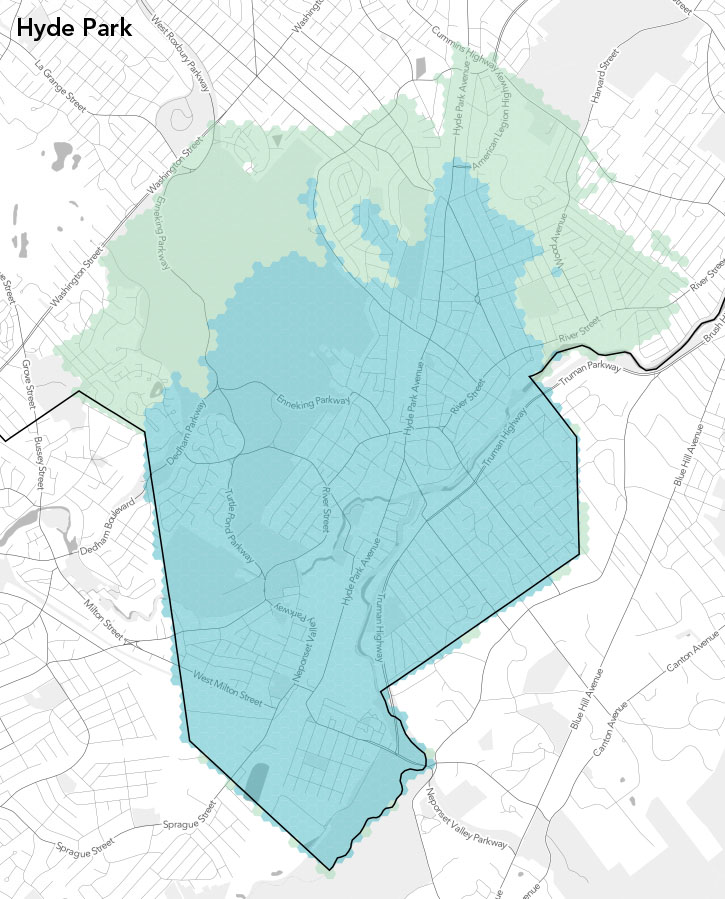

Hyde Park (n=42). We had few enough people drawing Hyde Park (or enough of them were clueless) that there is nowhere with more than 75% agreement. And to be honest I’m ignorant enough about Hyde Park that I can’t comment much on this one. It’s as outlying as outlying neighborhoods get in Boston. Anybody see anything interesting?

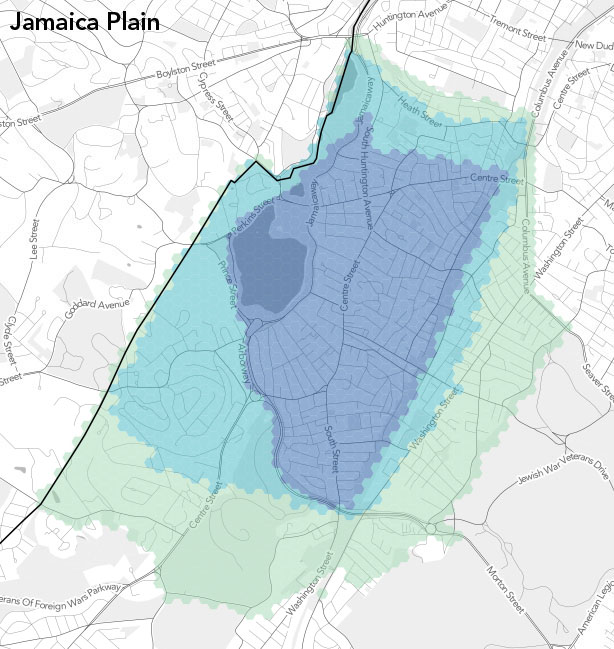

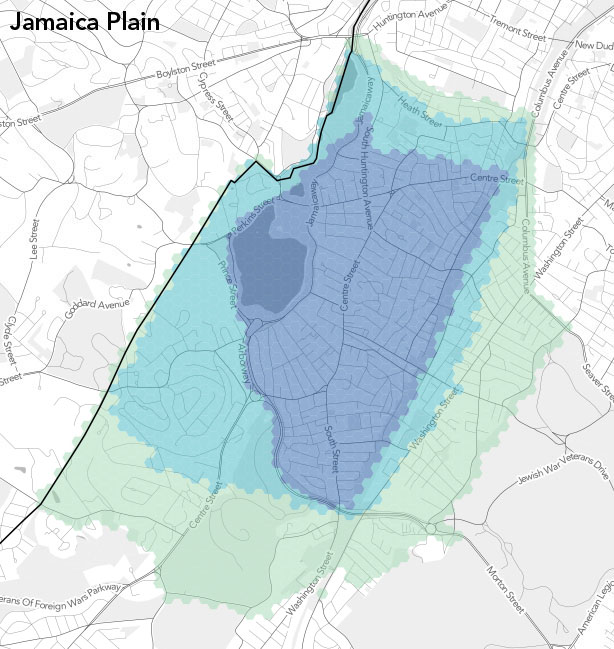

Jamaica Plain (n=74). There are ome fascinatingly well defined edges here. On the east side, people thing the neighborhood ends either at the Southwest Corridor, at Washington Street and then in a line up to Jackson Square, or at Franklin Park et al. and Columbus Ave. The 75% line on the west and south nicely follows the parkways, too (otherwise it’s just the city limits).

Leather District (n=76). Tiny neighborhood #2, easily lost between Chinatown and downtown. But hey, it has its own parking permit! There’s not a lot to talk about at the scale of our maps this time; some folks have it bleed over to Fort Point Channel but otherwise it’s mostly confined to a few blocks.

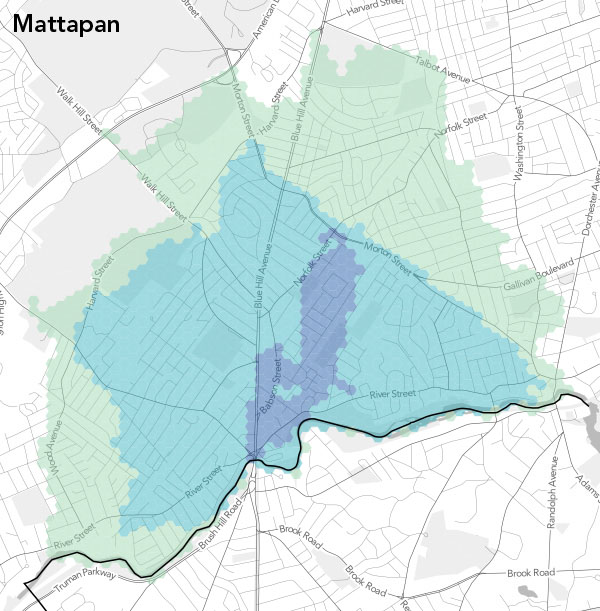

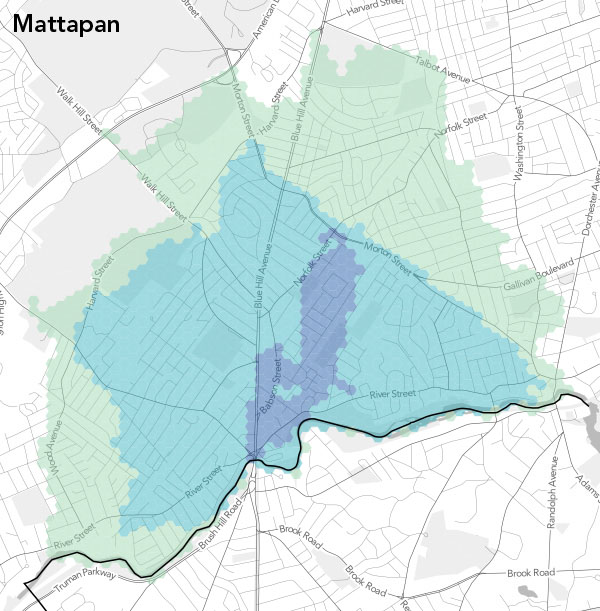

Mattapan (n=45). The 75% agreement is a very odd and small sliver, probably again due to a lack of data, or at least good data. But there are some clearer definitions at the other levels, for instance along Morton Street. As with the other southernmost neighborhoods, I can’t say much about this one personally. Comments are welcome!

Mission Hill (n=82). There’s a lot of agreement here below 75%, with the only real difference being the section below Francis Street. 75% agreement is only in a small area for some reason, not extending far from Tremont Street. Note that fewer than 25% consider the Longwood area to be part of Mission Hill.

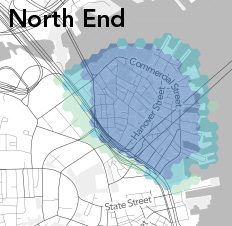

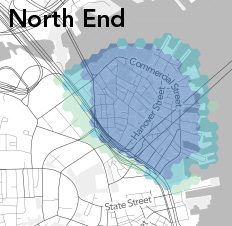

North End (n=151). Along with Beacon Hill this is one of the best-defined neighborhoods, being easily recognized by residents and outsiders alike. The only uncertainties seem to be parts of the Bullfinch Triangle and Christopher Columbus Park (where, it’s worth pointing out, there is a sign welcoming you to the North End), and all the piers. But even those places are mostly above 50%.

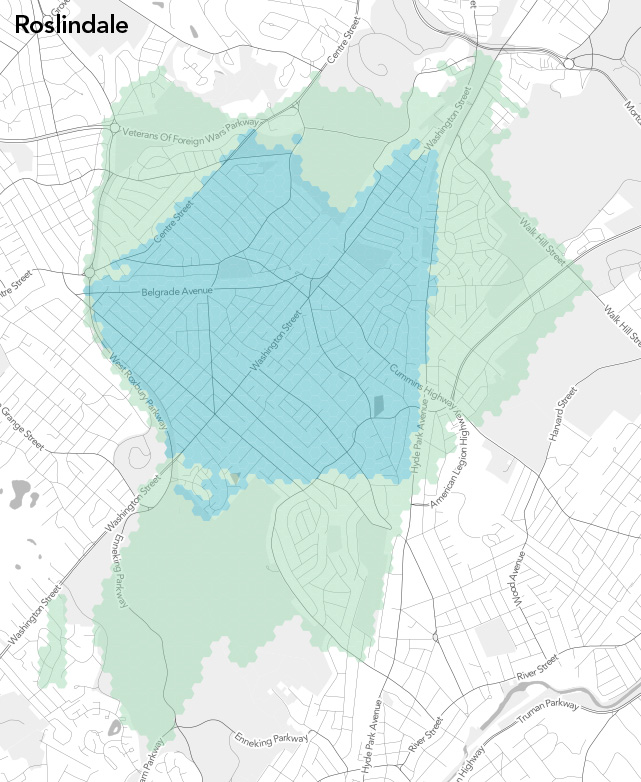

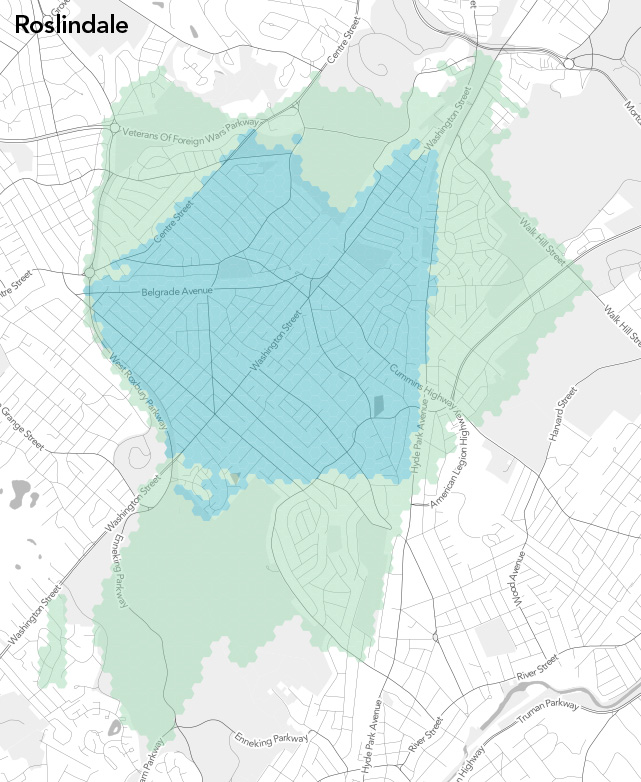

Roslindale (n=41). Wait, is Roslindale a real place or just the name of an RMV branch? Poor Rozzie had the worst data of the lot. It’s just, you know, down there somewhere in between other neighborhoods. What you see here is after some purging of especially bizarre data that were throwing everything too far out of whack. No strong majority here, although the 50% and 25% area are reasonably clearly defined in places. Some of the rest, though… who knows. There’s even a weird floating piece of 25% territory.

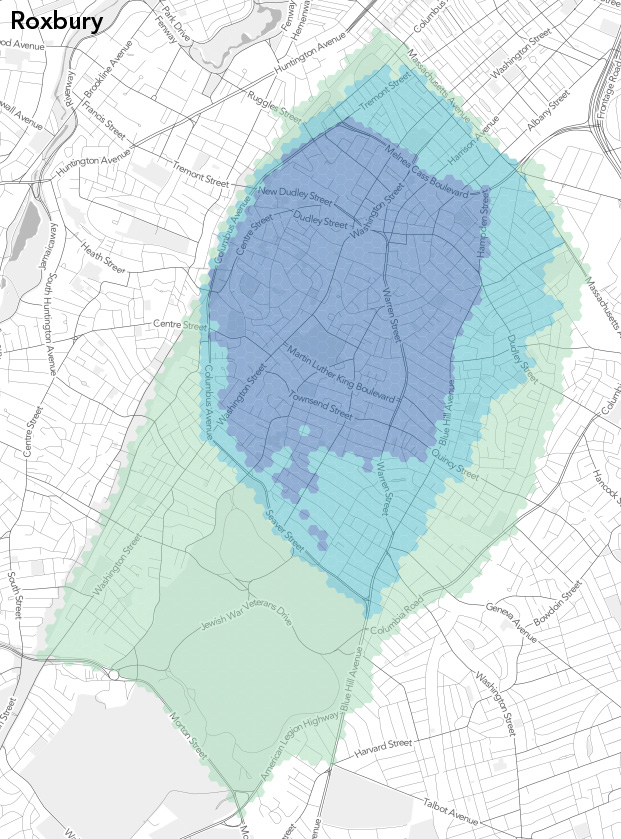

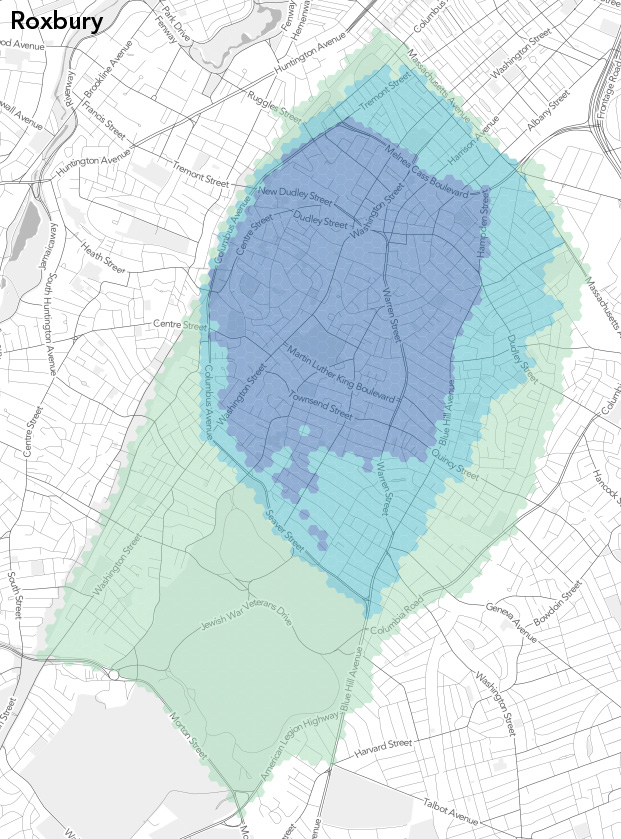

Roxbury (n=64). I personally think Roxbury is the most interesting neighborhood to watch in all this. It has uncertainties on at least three sides, and it and its neighbors seem to have reasonably strong identities to both their residents and outsiders (in contrast to some places that only have the former). The South End-Roxbury border debate is well-publicized, and the JP border gets fuzzy too. Mission Hill isn’t always even considered separate from Roxbury, and the border with Dorchester varies widely, as already mentioned. Apart from some weirdness in the south part of 75% land, there are some interestingly clear-cut camps here.

South Boston (n=92). There seems to be a lot of unity in Southie, apart from the Seaport area and a bit of the other end. Maybe it’s just because there’s not much to compete with: there’s water on most of three sides and something of a dead zone on the other. South Boston is a neighborhood that has grown considerably over the years thanks to landfill, and this map is suggesting that people’s idea of the neighborhood has mostly, but not entirely, grown with it.

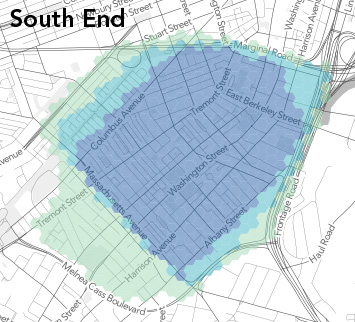

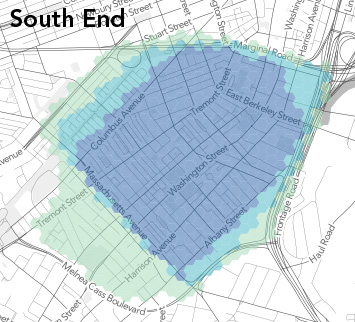

South End (n=116). Well, a lot of this has already been touched on by way of talking about surrounding neighborhoods. There’s a lot of agreement on Mass Ave as a border, despite the parking permit zone that crosses it (I think). Otherwise, the edges seem to match what we see in the adjacent neighborhoods, and within there is strong agreement.

West End (n=114). I suspect that to old timers and casual scholars of Boston, the West End doesn’t even exist; it was torn down in the 1950s. But something is there: a weird land of hospitals and towers in the park. Everyone agrees on a tight loop of roads defining the West End, but beyond that it’s harder to say.

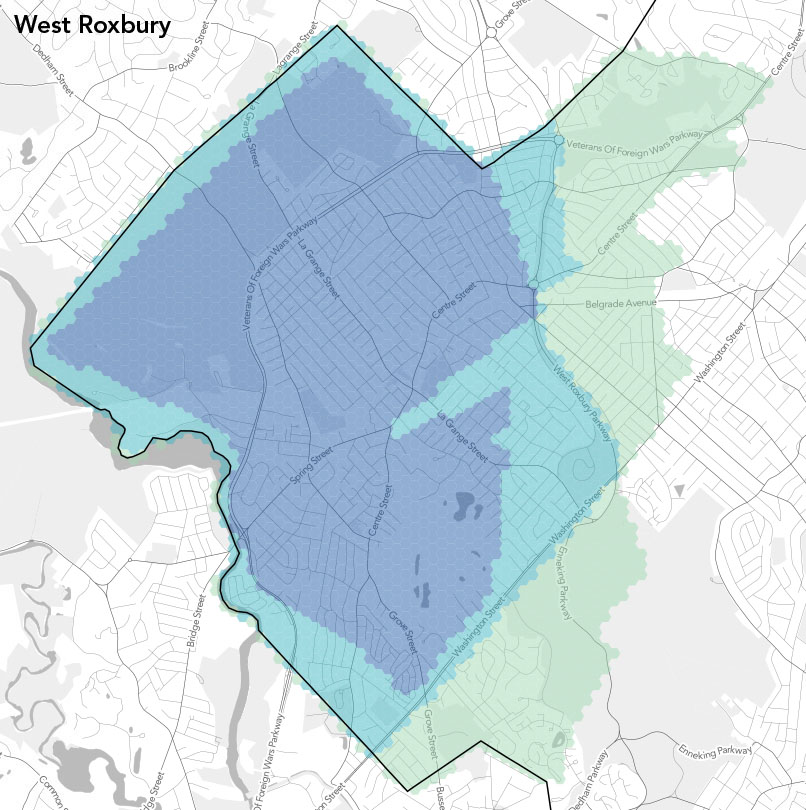

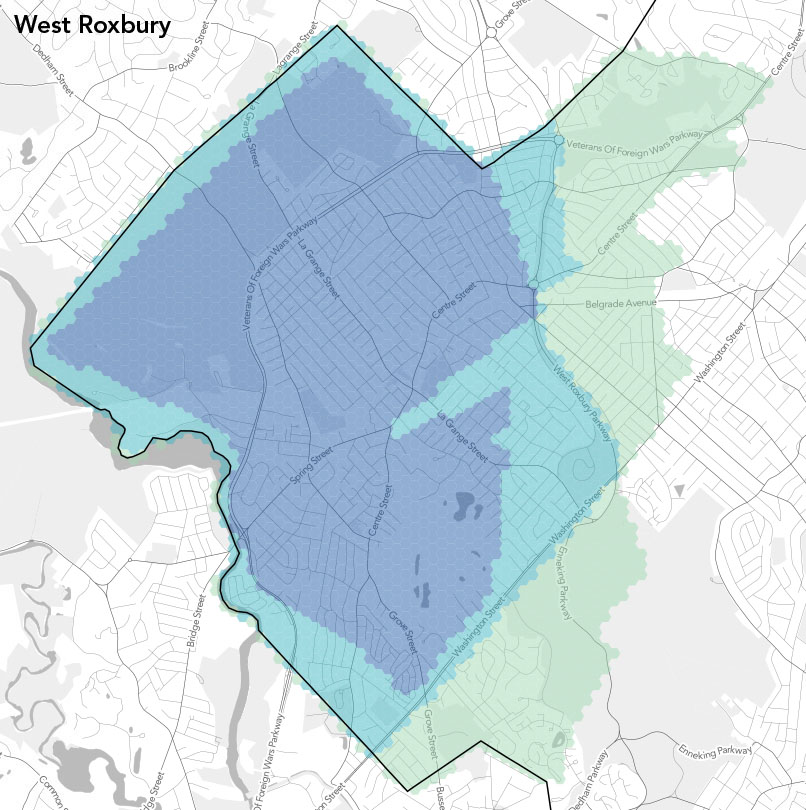

West Roxbury (n=43). The last alphabetically and somewhat fittingly one of the most distant neighborhoods, this one again suffers from a lack of good data. It has the fortune of meeting the city boundary for much of its edge, but away from that there are some funny shapes. And once again I don’t have much to add. We need more data and your thoughts!

What does it mean?

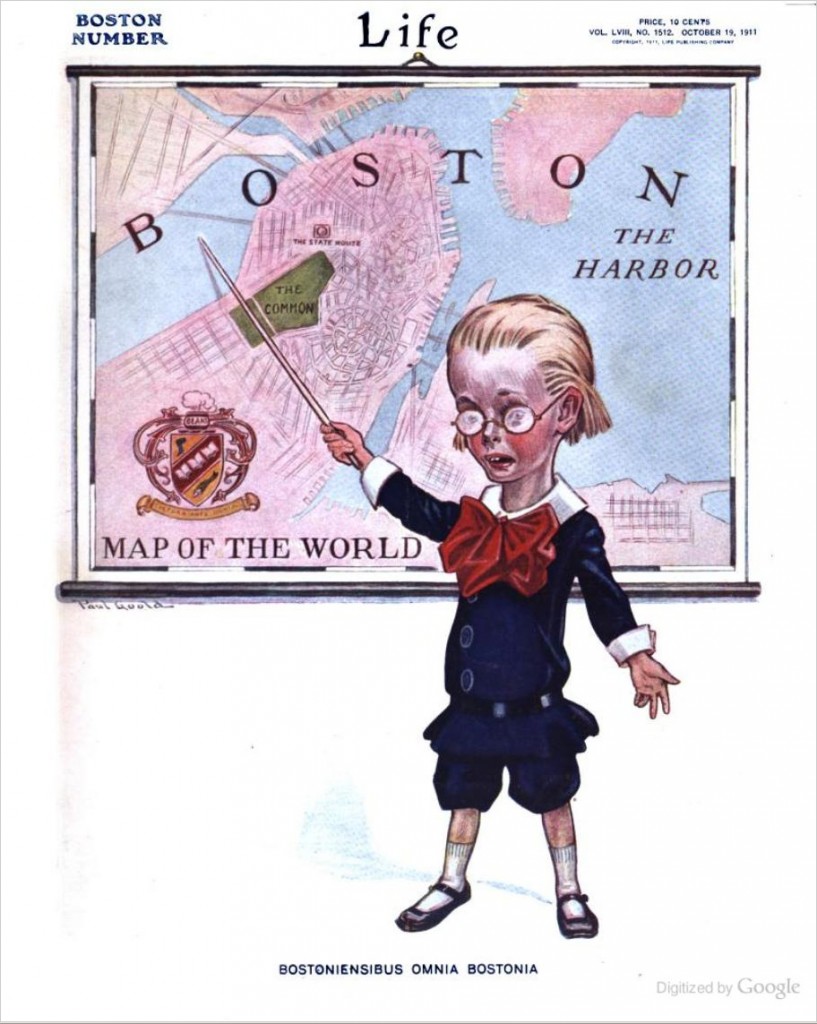

Although we talk a lot about boundaries, this post included, the maps here should also remind us that neighborhoods are not defined by their edges—essentially, what is outside the neighborhood—but rather by their contents. And it’s not just a collection of roads and things you see on a map; it’s about some shared history, activities, architecture, and culture. So while the neighborhood summaries above rely on edges to describe the maps, let’s also think about the areas represented by the shapes and what’s inside them. What are the characteristics of these areas? Why are they the shapes that they are? Why is consensus easy or difficult in different areas? What is the significance of the differences in opinion between residents of a neighborhood and people outside the neighborhood?

We’ll revisit those questions in further detail in future posts, and also generate maps of other facets of the data. Next up: areas of overlap between neighborhoods. Here we’ve looked neighborhood-by-neighborhood at how much people agree, so now let’s map those zones that exhibit disagreement. Meanwhile, thanks so much for all the submissions for this project; and if you haven’t drawn some neighborhoods, what’s your problem? Get on it!